I do not like to know the plot of a film before going to the cinema or read reviews of a book before reading it. The opportunities for me to be surprised are so few that I don't want to miss out on the surprise of finding out, for better or worse, what is in store for me.

I do the same with races: I gather some superficial information and then make my own mental plan, at least I try to plan my training to cover the difficulties of the race. It's a very subjective method of training (#cazzomannaggia) that sometimes works, and sometimes leads to epic failures, especially when my idea is very different from reality.

I followed this strategy for the PTL too; on the other hand, how do you prepare for a race of over 300 km and 26,500 m of positive elevation gain?

My previous benchmarks fell much shorter than that: 26-odd hours for the UTMB and 33 hours for the Spartathlon; at the PTL, if it goes well, I can finish in a time that is 3 or 4 times as much. The magnitude of the feat looks enormous.

Fortunately, the anxieties and fears fade a few days before the start, when, by now, I’ve done all I could do and an insane curiosity to find out what lies beyond the start line assails me. What I like best about these ultra-adventures is precisely the discovery of the unknown.

Fortunately, there are not many people in Chamonix yet. The big circus is yet to open and at the briefing, run by the PTL committee (different from the UTMB one) there is a quiet village race atmosphere. With very little fanfare, we are told that there will be difficulties such as chains, ridges, rocks - but nothing we need to worry about.

I'm not very nostalgic but there's little we can do about it: every time, the start at Place Triangle de l'Amitié in Chamonix, for what it represents for the Trail Running movement, is always a great thrill - even for three old, worn-out trail runners like us. Yes, because this adventure is a team effort and ours is a team of three.

Right from the start it is clear that we love adventure: we have never met before the start and we have never looked at route maps. The other teams seem to proceed, as if remote-controlled by a satellite, without looking at the route to be followed. We, on the other hand, decide to check our instruments (the route is not marked and we follow a GPS track) and we convince ourselves that everyone is wrong and we proceed on an alternative path before realising our mistake of presumption. We still have to get to grips with the instruments but there will be plenty of time to do so.

My rucksack, thanks to the experience gained at the Marathon des Sables, is heavy but manageable; Roberto has a large hiking rucksack that I have never seen him with, and Luca, well, Luca can easily compete for the prize for the heaviest rucksack of all, I think he has twice as much as the required equipment plus something extra. The other teams have backpacks barely bigger than those for the UTMB and have tried out the route almost entirely. Where we get lost or take hours to figure out where to go, they pass us without hesitation, exactly where we should have gone too, leaving us speechless.

Right from the start, the race shows its true colours: between two paths (when there are any), the route always follows the harder one.

We often waste a lot of time looking for the route, simply because it seems impossible to go where the GPS track goes.

We soon realise that this is the spirit of adventure and we somehow appreciate the schadenfreude of constantly putting competitors in a pickle. We give up competing with other teams and enter some sort of (psychological) challenge with the organisation of the race. Our thoughts soon become: 'you want us to go that way, fine, we'll go that way and may the last man standing win'. It sounds silly, but this change of perspective helps us to remain vigilant, always ready to make decisions, because we know that around the corner, behind a smoother stretch, there will surely be some difficulty waiting for us.

I don't know much about such long races and I rely on my teammates, who have already completed several of them (they are two of the most accomplished ultra runners). I am very curious to see what will happen when I step out of my comfort zone.

The first night we don't sleep, it is a beautiful night, warm and clear, the starry sky is beautiful and I am convinced that this is the right strategy.

Dawn is coming, we are happy to have found the path where there seemed to be none. Others have opted for the ridges, which in our opinion could end in an impassable section. In fact, as we laboriously climb up the valley along what vaguely looks like a trail, we turn around, startled by the sound of stones rolling off the ridge and see Iker Karrera and Zigor Iturrieta nearly crashing down on Roby.

As very often happens, after so many hours of on our feet and so little sleep, time becomes liquid and it is increasingly difficult to perceive its flow. The traditional distinction between day and night no longer exists, some moments last an eternity while hours seem to fly by.

We cross hills that have never been traversed by anyone before us, where we do not even see the tracks left by those in front, we scramble on rocks so steep that we have to climb to avoid crashing into each other, and we descend valleys amidst blueberry plants so tall that they reach our knees; I must have eaten half of those blueberries.

We see so many wonderful things that our brains struggle to memorise them.

With a few hours’ delay on our 'give-or-take-metric' calculations, we get to Val Veny, the first of the two life bases. Relieved to have reached this milestone, we happily lose ourselves in chit-chat and with perfect timing set off, after retrieving our via ferrata kit, towards the most technical part of the entire route, in the dark. I opt for a pair of Spin Rs shoes, we have to climb up the old via ferrata to Rifugio Monzino and descend from the new one; the choice turns out to be the right one for rock climbing.

Where we expect to find a bridge and normally there would be a nice volunteer, we find only a pole with a trail marking (we will only encounter three on the entire route) and a stream. It is dark and, illuminated by our headlamps, the creek seems very impetuous; we see no other teams, so to be safe we call the organisation, and they tell us that there should be a rope. The rope is nowhere to be seen. There is no other way, we ford the creek and cross to the other side. In the darkness, Mont Blanc looms huge in front and above us. A little later we find a rope tied to two rocks on the sides of another creek. We thank the organisation for such generosity. Roberto tries to pull the rope, which, being elastic, makes him swing and dip his butt in the water. We decide to jump and land on the opposite side. It is not easy to find the beginning of the via ferrata in the dark, among the old ropes dangling from the wall.

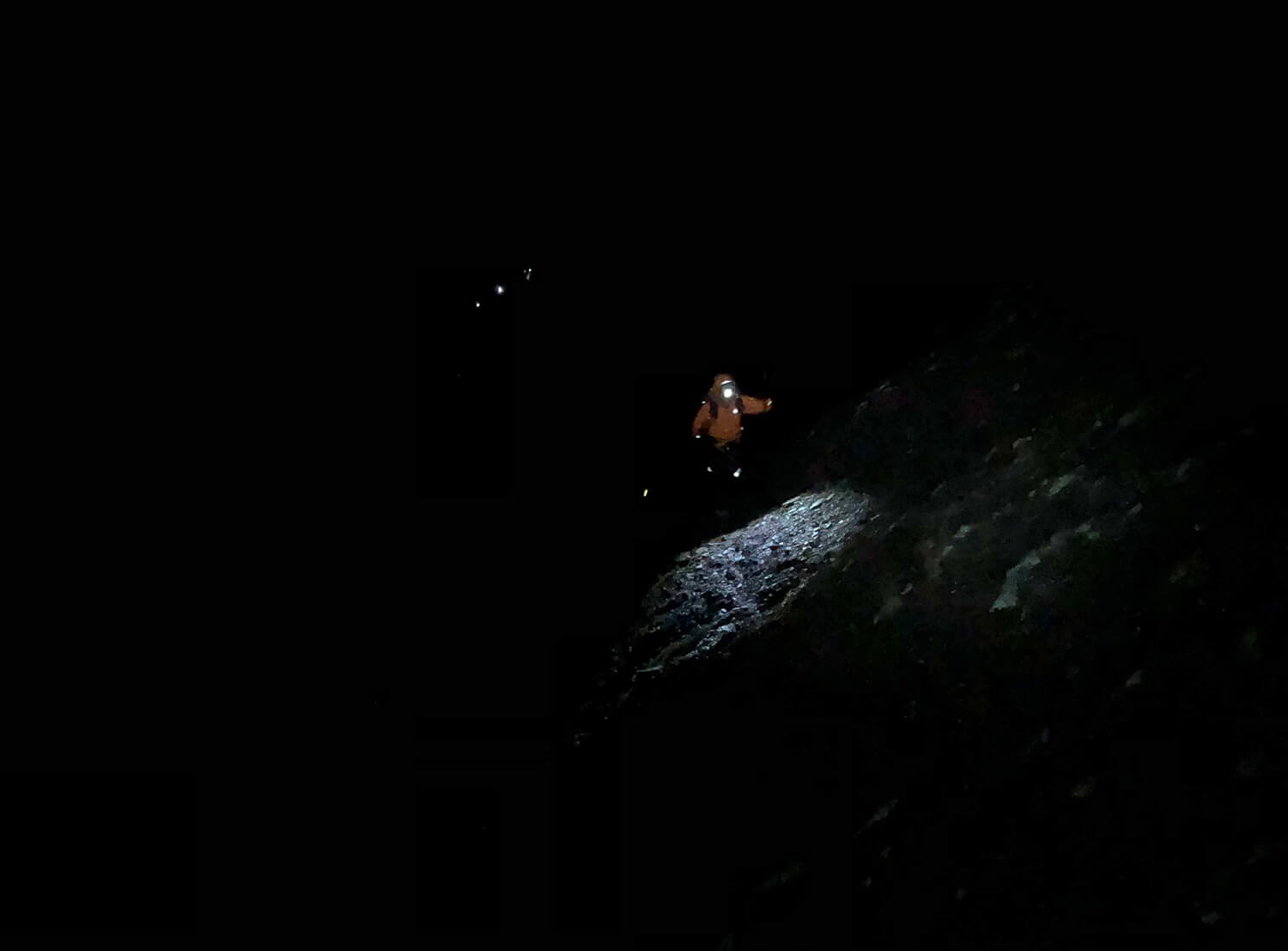

We begin our ascent; it feels good to pull ourselves up with the strength of our arms, easing the strain on our tired legs. Fear of heights and adrenalin drive us to climb fast between rocks, bolts and steps, and we reach the end of the via ferrata in the middle of the night. The wall is so steep that we see, in the valley and on the via ferrata, the other teams who have followed the route lit by our headlamps. The full moon begins to give us a glimpse of the Bruillard glacier in the dark, and we eat something, happy to be there, halfway between the sea and the summit of Mont Blanc. We carry on but cannot find our way to the refuge, an obligatory waypoint. We see it on our screens but it seems to be beyond a vertical wall that seems insurmountable in the shadow of the moon. I try to climb further up to look for a perhaps easier passage, Luca tries the wall and Roberto studies the roadbook. All three attempts prove fruitless. The place is very beautiful but we have been there too long, and I look for a cell signal to call the refuge. Incredulous and a little foggy from tiredness, we follow the hut keeper's indications towards the wall that seemed insurmountable and magically we find some old yellow markers that guide us to our destination. The other two teams, who have surely slept for a few hours, are catching up with us. We put our signatures on the poster at the refuge and discover that we are the fourth team; we know that this means nothing and that we are just at the beginning, but we wake up and run to the attack of the ferrata on the descent route. We proceed quickly - Luca and I, in order to see where Roberto has ended up, illuminate the void beneath our feet with our headlamps, standing on a makeshift step, made of a metal rod driven into the rock. I don't know about Luca's legs, but mine begin to shake, in a mixture of fear and tiredness and I start to use the second lanyard as well. All the equipment, including the helmet, was needed. With a beaming smile, we catch up with Roberto and together we put our feet back on the valley floor.

We swing from periods of extreme lucidity, stimulated by tension and fear, to moments of clouded tranquillity. In fact, what seemed like a simple crossing of the Miage glacier turns out to be a real nightmare. We awkwardly proceed on the unstable scree and we struggle to get out. I insistently suggest a break to rest, but the icy air descending from the glacier over Lac Combal prevents us from doing so. We arrive at the Elisabetta hut at dawn on the third day, have a quick breakfast and, despite there not being any sleeping room for us competitors, they very kindly offer us a room, where we opt for a break of just forty-five minutes. Ever since I was a child, I have always had trouble falling asleep, I usually sleep very little and badly. I dread this moment very much. I am afraid, having so little time at my disposal, that I will not be able to sleep, but lifting my feet off the ground at last after three days, on the other hand, throws me into an intense sleep.

At the sound of the alarm clock we quickly get ready, as if we’d been programmed for this type of routine, and in what looks to us like absurd mayhem, made by the hikers packing their large rucksacks, we resume our walk, where we find peace. Our life has been reduced to the essentials: eating, sleeping (a little) and following our route. In our rucksacks we have what little we need.

Now, due to fatigue and sleep deprivation, although we do not communicate, we act as one single-cell organism: the needs of one are those of all three.

The experience is so intense that it is difficult to have coherent thoughts. Memories, along with unseen but memorised images, mingle and surface in random order, while some bits are a black hole.

The part that leads us to the Robert Blanc refuge is very nice but the weather is changing and thunderstorms are expected, so we only make a brief stop which essentially means eating and not sleeping. We flee quickly (so to speak) with two other teams, including one composed of brother and sister. Him, I nickname Ivan Drago (the one from Rocky) because he is always emotionless in the face of difficulties. I try to imagine their story: what could be the reason that pushed them to undertake such an adventure? They know the route very well, they have already tried all the difficult parts, he is a GPS wizard, she is progressively more and more tired; we sleep less, but when we lose time looking for the route they always catch up with us. When the first storm hits us, in unison, we pull out our secret weapon, the poncho. Quickly without stopping we put it on over our rucksack and are protected like a snail within its shell. This ritual would be repeated an infinite number of times before the end of the race.

Here, there is no race management to make decisions for us in the event of bad weather, we have to make them ourselves.

We are alone, there are no volunteers to show us how to tackle difficult rock passages. We pass through areas so remote that even the classic mountain cairns become a mirage and those few that look like cairns are, in reality, remnants of some landslide with no marking value. We pass through valleys that have never been traversed by human beings, where paths are totally non-existent. This is the spirit of the PTL.

There's no point in acting like superheroes, we're not; tiredness creeps in, joints creak, but what suffers most from all these kilometres and hours are the feet. They hurt, especially in places that are normally little stressed by running. The long traverses over rocks cause pain on the outside of the heel. From here on we’ll have to gauge our ability to withstand the pain.

The race is so complex that we explore almost all our physical and mental limits.

Trusting that a few short fifteen-minute breaks will be enough for us, we eat at the Refuge de la Balme and in the middle of the third night we set off towards Pierra Menta. The fog is thick and humid, illuminated by the headlamps; this takes us to a state of dreamy drowsiness, making our decisions on what route to follow very difficult. The situation is complicated by the numerous markings of other races on the mythical mountain. It is raining, we are cold, we get dressed, we change the batteries of our headlamps, but we cannot find the course and we lose a lot of time. We are joined by another team in the search of the pass to cross. Shortly afterwards, Ivan Drago and his sister (who have slept for at least an hour) also arrive. The scene is, more or less, this: it's three o'clock in the morning, it's raining sideways, there are five of us looking for shelter on the south slope, shivering and clad with everything we had in our rucksacks, we have all the possible technological instruments in our hands. As if nothing had happened, he overtakes us and throws himself down the slope that neither we nor the others had dared to cross. On the other side, a strong northerly wind was blowing; Ivan stopped at a certain point, and we smiled because we thought he realised he’d made a mistake, but instead he took off his jacket and, wearing only a T-shirt, started to descend again as if nothing had happened. What a star!

After that, the scenery changes, dirt replaces stones, we breathe a sigh of relief, but it will be very short-lived: because of the mud, the ridge that we must pass is barely viable.

We are over halfway through the race and so far, we haven’t had any major problems. In this section, however, I am literally collapsing. I can't stay on my feet, or rather I keep walking but without realising I fall on my leading leg; the instant I fall I wake up and stick my pole in the ground to avoid falling. Two more steps and I collapse on the opposite side. I see myself from the outside, asleep on the edge of the path; no one notices and they leave me there. I am out of my comfort zone. It is an experience I have never had before. I don't know how long this real nightmare has lasted, but I know that I cannot stop in the mud, in the rain, I have to reach the next refuge. I just concentrate on this, even though there are at least twenty kilometres to go. Fortunately "Ivan", who is leading the group, stops. For once, even he doesn't seem convinced that we can pass. Welcome among us mortals.

In turn, we make a few attempts to find alternatives, but they all turn out to be impassable and off course. We are joined by another team who, using their poles as ice axes, manage to get through. The mud is like molasses, so to decrease the risk we put on crampons (thank you Nortec) and what seemed impassable turns out to be manageable. We fall behind and are about to lose contact with the group. To wake myself up I run ahead so I don’t lose sight of the others. I still manage to run and it is almost liberating, after so many hours of walking. I am alone, halfway between the group ahead and my teammates, to whom I signal with my headlamp to show the way. During the day and in good weather this ridge must be wonderful, whilst at night with the rain I can't wait for it to end. I catch up with the group but I don't see my team, I stop and while I wait for them, as dawn creeps up on the fourth day. It is always a magical moment and it helps me stay awake. I try to calculate the hours of sleep and I count four; strangely enough, I cannot calculate the days that have passed. In theory, we could have arrived in Chamonix on Friday afternoon, we had imagined a triumphant arrival an hour before the start of the UTMB with a full crowd cheering on us. But dreams are often far removed from reality, we still have more than 100 kilometres to go and 10,000 metres of climbing to do.

At Beaufort (second and last life base) we eat. I, not sure why, also take a shower and sleep what has now become our standard dictated by Roberto for long stops, our 45 minutes. Roby's standard for short stops is 15 minutes, sometimes reduced, to my disappointment, to 13.

In the middle of the fourth night, we set off again regenerated; it seems that our bodies have adapted and can get by with very little. I feared the restarts, but instead, diving back into nature after being indoors for a few hours is almost liberating. We have become like those tramps who, allergic to convention, must constantly take refuge in nature.

The race is so long that the experience accumulated in the first few days comes in handy later in the race. We climb quite well, by now our navigation technique is tried and tested: we follow the track on Luca's Garmin, when we reach a fork in the road or he has a doubt, I open my Cartograph app and head in a different direction from the one in which Luca is moving. This way we quickly realise which is the right direction. We are not as fast as those who have already tried the route, but we manage to find it fairly quickly. Like in the last three nights, as we climb, we first reach a layer of fog and then it starts to rain. In this area, the mud has a clay-like consistency and we also slip on the flat. The instinct accumulated in so many races (we have tried to count how many the three of us have completed in the last 10 years and it is more than 1,000) pushes us to run. At this point we are joined by a team that comes out of nowhere (or rather out of the mist). We are now stable around fourth place in the rankings, however little this counts, since there is no official classification, but it serves as an incentive for us to stay focused. At the magnificent hut du Petit Tetraz, Luca and I sleep our 15 minutes, while Roby stays to chat in the lounge. We set off again quickly, making the most of our stop. We realise that we are much slower than expected, due to the difficulty of the route and we try to make up for lost time. On the next climb it is Roby who asks for a time-out, he is about to switch off and we sit down on one of the rare benches that line the road. I’m just falling asleep when he springs up, walks for a while then sits down for an indefinite time, which seems very short to me, then leaps up again. He doesn't want to talk, he proceeds alone with his demons. We follow, so as not to lose sight of him. Observed from behind, he looks like a disjointed puppet about to fall at any moment. Then dawn comes and we regain a good pace.

Near Col Des Aravis we unsuccessfully try to buy food. As we continue, I feel that my achilles tendon in my operated foot is becoming inflamed and something is swelling under my sock. So far the pain and problems have always been minor and bearable, whereas now I know it is something that can only get worse. There are about 70 kilometres to go, which at a PTL pace translates into a day and a half. I see all the effort I have put in so far as useless and the possibility of finishing the race vanishing in a second. The stakes are very high, normally I would stop, but I decide not to give up. I know that I will pay the consequences. I try to find some relief by using the pole as the same time as my right leg while blocking the tendon movement with the calf muscle. The pain is so sharp that I lose lucidity, I no longer know whether I should eat or sleep. I rely completely on my two teammates for the simplest decisions.

We are at a standstill, I wake up from my bad thoughts when I see Roby going in one direction and Luca in another. I choose a third way, but we just can't figure out where to go. I remember Roby saying that if we go up then we won't be able to go down, and if he says so it must be true, in fact no one contradicts him. We weigh up all the possibilities, evaluating the pros and cons, and in the end agree on the passage into the gully, in the hope of not having to go back. When we finally find the route, two teams, who are descending towards the bottom of the valley, see us and immediately turn around. The passage is narrow and a bit of a mess, but we are happy to be out of that uncomfortable situation. We arrive at a point where erosion has carved a magnificent hole in the rock from where we can see the whole of the adjacent valley and we understand why the organisation wanted to make us work so hard; the view at dusk is gorgeous. We have to climb down but we try to do it quickly because in the distance we see a storm coming. Shortly afterwards it starts to rain and with the darkness it also starts to get cold. We can't tell how far we are from the refuge. Under the storm, the darkness is thick, the ground is very slippery and I am very cold. The track deviates abruptly from what appeared to be a trail. We have to follow a traverse that becomes steeper and consequently slippery. There is a light on the other side of the valley but the track does not seem to go that way. I turn to look to see if the two teams to whom we have shown the way are coming and I see, I'm sure of it, hundreds of little lights coming down the path and heading towards the light in the valley. Hundreds of torches chasing each other like a swarm. The spectacle is astounding and I call the others to give a scientific explanation of the phenomenon. A village festival, magnificently orchestrated by the shepherds of the valley, who have placed small LED lights on the sheep's collars as they return to the fold. Roby and Luca nod but are focused on finding the route because the weather is getting worse. We see lights above us and lights that seem to be coming towards us. It's hard to know which way to go. We decide to follow the track even though the slope on which it passes has collapsed. It seems impossible for us to move on.

We send our position with the GPS spot and call the race HQ; they tell us that the guides are coming up to divert the route, in order to avoid the landslide and we are right in the middle of it. We shout and swear at the lights that are approaching. They shout at us to move on and get out of there. Easy to say, a little less so to do. I can't take it any more, I'm the first in line and I concentrate on not slipping but once every two steps I slip, I use my poles as ice axes but they're not enough, sometimes they also slide on the slope. I want to stop and put the crampons on, but I can neither sit down nor lift a foot to put them on without slipping. I increase the power of the headlamp to the maximum to try to figure out where to put my feet and unfortunately I look down: I can only see an overhang the overhang and far below, even if one can't see it, a creek whooshes by. I can't proceed in a straight line and I am gradually descending towards the end of the landslide jumping off the overhang. I suffer from vertigo and often in situations of precarious balance over the void I think that rather than continue to suffer it is better to jump, but these are only fleeting thoughts. This time it is not just vertigo, I really am afraid of falling. I have to do something to get out of it, my legs are shaking. I tap the ground with each step before loading my weight on it, I point the poles holding halfway up the one above me (thank you NW) and the one below me from the top trying to distribute my weight as best I can before lifting the other foot. I think about nothing, I don't think that I can fall and slip, I am totally focused on the repetition of these elementary moves, I don't hear the torrent screaming below us, I don't see the rain and the mud flowing, there is nothing but the cone of light illuminating my feet. Slowly after what seems like an interminable amount of time, the slope decreases and I begin to run away from the danger I have just escaped. When I arrive on the path down from the ridge, I turn to see where Luca and Roberto are, but all I see is darkness. I was convinced that they were behind me. I shout in their direction but my voice is drowned out by the rain, the wind and the torrent shouting back. I do not know what to do. If I stand still I’ll freeze, but I don't feel like going back into that hell. I shout and signal to the guides who are going to divert the path to avoid the landslide I just came out of. They don't hear me. Maybe they have turned back, maybe I have come down too far. I must retrace my steps, we cannot get lost. Finally I see a light coming towards me, it can only be one of them. I light up Luca's face and see the fear drawn on his face. He, who is always emotionless, is pale and looks very tired. Neither of us says a word, we can’t see Roby. After what seems like an eternity to us, he finally emerges from the darkness. With crampons on his feet. I won't even describe his face, he mumbles something about the limit, about death, he says that his life has passed before his eyes but he is also amazed to have seen his mum and not his children. We look at each other for a moment, all three of us looking into each other's eyes illuminated by the headlights, and we realise that we have taken an enormous risk and that we have fortunately lived to tell the tale. It is a dramatic moment but also a very intimate one. We are on the edge of a ravine, in the rain, with an icy wind blowing over our heads, and we are happy to be together again.

In really critical situations we manage to pull out a primal survival instinct that instantly processes all the information, while our experience helps us to stay focused on the way out.

When we reach the path we see the other teams that have passed through the ridge who already descending, we say goodbye to them, we don't even need to say it, but our race ends at the Col de Doran. In religious silence we descend and sadly make our way towards the hut, the rain finally stopping. Everyone is absorbed in their own thoughts. The tension slowly subsides.

Sometimes at night, due to fatigue, the shadows turn into fantastic animals and I seem to see drawings on the white stones scattered along the valley that look as if they were drawn in ink in a style which reminds me of the anime character Captain Harlock: pirates, skulls, spider webs, each one more beautiful than the last. I think it would be nice to make t-shirts for Wild Tee. I imagine the shepherd (a real artist) painting them while the herd is grazing.

We enter the hut and say nothing of what happened, we decide to take a break for a few hours to put the memory of this bad night behind us.

The next day the sky is clear and we continue our walk with renewed bliss. We want to end the tour in no hurry, enjoying every metre of the remaining kilometres.

After what we have been through, the normal difficulties of the race make us smile and we jokingly head towards the 2000 metres of positive altitude difference that await us at the two hundred and sixtieth (it is hard even to write it) kilometre mark.

The tension vanishes, time no longer exists, the pains disappear and it is just the three of us and the mountain. We know that, sooner or later, we will reach our destination. We begin to visualise the arrival, or rather, the image that so many times works much better than the finish line banner: a nice lunch in the sun, washed down with good beer, taking our time to put our thoughts in order.

The difficulties are not over, but the accumulated experience comes in handy to tackle them with a healthy amount of irony. Yes, because climbing the half-frozen Passage du Dérochoir in the fog and laughing like fools takes a sizeable amount of it.

The trails before and after the Refuge de Plate (the hut keepers are fantastic and we had one of the best lunches of the week) are the epitome of Trail running, a perfect #todaysplayground and, despite the 280 kilometres our legs have already covered, we run them all.

We are so used to choosing the harder route that we continue on an exposed ridge, going the wrong way, instead of descending on the trail.

I feel good, tendon aside, but that is outside of my thoughts right now, it is a subject I will address in the days to come.

A beautiful sunset greets us and pushes us towards the final ascent to the Col de la Brévent. On the other side Chamonix awaits us, where the arrivals of all the other races have taken place during our absence. We are almost afraid to leave the silence and solitude of what has been our “planet” for nearly a week.

I was very afraid of the metres of altitude difference; instead, I still climb well, I could even push harder. Being able to quell my doubts, to climb at a good pace, is a huge satisfaction.

Once again the magic of the ultratrail is fulfilled: what seemed impossible at the start turned into a huge life experience.

PS: the next day, with a huge lack of sensitivity, my fellow adventurers totally wrecked my illusions by telling me that there was no running herd of sheep with lights. Very often the lack of sleep causes hallucinations that take the form of our deepest fears, the logs turn into bears ready to attack, the shadows into monsters that chase us, the woods into endless tunnels. It was the first time they took such a poetic form instead.

In 135 hours both Roberto and I used two pairs of Bryce shorts and three t-shirts each. In addition, we tested the new Rockies socks and the second Appalachian layer, which will be released in 2019.