THE TRUE NATURE OF TRAIL RUNNING

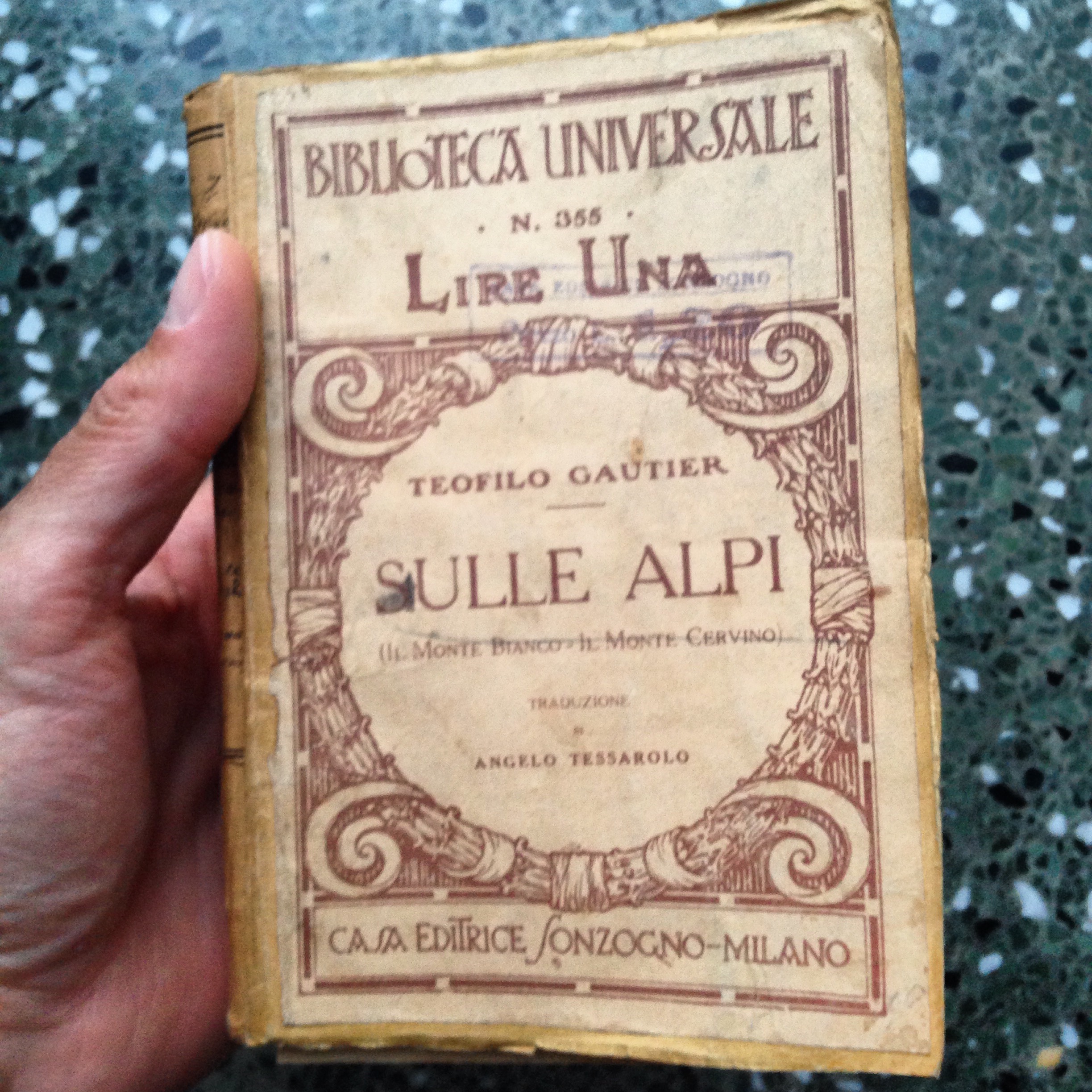

A few years ago, I found an old book that belonged to my grandfather, describing a tour around the Matterhorn. It took me quite a while to get organized and set off on this adventure, the solo Tour du Cervin. Hiking and running for so many kilometres, while alone and in complete self-sufficiency, made the trip even more special. I was focused on the path to follow, but also careful not to miss a single moment of this precious experience. The tour was demanding, the terrain technical and, at times, very difficult; the average altitude is 2400 m, and to complete the tour you have to climb over four mountain passes above 2800 meters a.s.l. and four above 3000 m. The distance to cover is 159 km and the elevation gain is 10400 m, but mere data won’t give you a true picture of what can be experienced during a 31-hour long hike.

SUNRISE

The very moment in which the sun illuminates the peaks with its first beams is always magical. First the higher peaks, then the lower ones, and finally the valleys are flooded with its golden light. I tried to move as much as I could during the late-August 15 hours of light between sunrise and sunset. This is the first picure, shortly after leaving Cervinia.

SILENCE

Especially in the early hours of the morning, silence in the mountains is almost absolute. I always try to proceed without making any noise, as if tiptoeing, so as not to disturb.

The ascent and descent from the Col de Valcornière are truly demanding and I start doubting my ability to complete the feat. The terrain is difficult, sometimes exposed; there is not a living soul around and I feel a little lonely. Even though I hardly ever think about it, this is one of those times when a thought springs to mind: if I fall and get hurt, I might have to stay here for a long time. I proceed very carefully until I return to a trail, where I start running as fast as I can, as to escape from the danger I just avoided.

THE PERSPECTIVE

In the mountains, as in life, it's often all about perspective.

At the beginning, the goal seems unreachable.

When we finally get to it, we realise we’re only halfway there.

At the end of the way, when we reach the highest point, what seemed so difficult before, appears simple to us.

After all, it is only a matter of points of view. And if you go by the Nacamuli hut, during the ascent to Col Collon, get in and eat a slice of blueberry cake – believe me, it’s worth it - because then you cross into Switzerland.

APPEARANCES DECEIVE

What appeared to be the most difficult and risky section of the entire journey turned out to be actually quite easy to handle. In the photo you can see the Arolla glacier, or rather what remains of it. The glacier, gateway to Switzerland, on current maps, is still drawn to the point where I am taking the picture and in theory is more than three kilometers long; in reality, now the ice area is not more than one kilometer long. I’d been very worried about crossing it, not being able to proceed while roped to someone else, but once I arrived on the huge moraine left by the glacier’s slow but inexorable retreat, I simply felt like a helpless witness to this effect of global warming. However, I had brought my Nortec crampons to cross two glaciers.

THE SUN

I’ve ran out of water. The sun is cooking my head. Damn me, I forgot my hat at the start. Finally I meet some hikers and ask them if there is water at the Col de Torrent or on the descent. In various languages they answer NO. There is no better way to increase your thirst than knowing that you cannot drink. My 1.5 liters of water have practically evaporated. The sun dries my skin. My neck is burning, I turn towards the valley and I see the 4-thousanders behind me. I feel like laughing, I’m on a pass called "Torrent" and there is not even a trickle, despite the almost three thousand meters of elevation. I have no other hope than move forward and hope to find water...

As soon as I get over the pass, I see Lake Moiry at the bottom of the valley. From above, the water of the lake looks heavenly and wonderful: if I had a paraglider, I would launch myself from here. During the descent I make a thousand detours to look for water in all the fountains and troughs for cows, but not a drop comes out of the pipes. As I descend, I see cars on the road around the lake and when I reach it, I find a rather posh bar-restaurant where I enter quite tired and smelly. I ask for information on how to get to Zinal as quickly as possible. They must have thought that I was on a bicycle, because they show me the asphalt road. I try to explain myself better by showing the map and they tell me that for the Col de Sorebois it is very long and that they have never done it. I thank them for the confidence boost and I leave.

ZINAL

Here ends the historic Sierre-Zinal race. I laugh at thinking about myself trudging on the same trails where Kilian runs towards victory. Luckily, I proceed in the opposite direction, following the yellow signs marked SZ.

THE MOON

It starts to get dark. But when the moon comes out, one feel less alone at night.

I had planned to arrive at the Weisshorn hotel by 9 pm. The hotel keeps the kitchen open until that time, so I wanted to eat something warm before the night, but I am late and the 10 km and 750 m elevation gain from Zinal seem endless to me. In fact, I arrive as they are closing for the night. I can only get some fruit and water. I go out, it's getting cold and I have to look for a place to rest for a while. Shortly before getting there, I had seen a wooden house that seemed abandoned. I find it but it’s very run down and the roof is falling apart. I decide to stop outside on a kind of bench, I got cold and I wear everything I have: shorts, leggings, windbreaker, short-sleeved shirt, long-sleeved shirt, light down jacket, hat and gloves. I feel sick and I can't eat much. Making a quick inventory of my food supplies, I realize that I haven't eaten much because of the heat. Instead, now I have chills and my feet are frozen. I can't sleep, even by counting the lights of the houses that one by one go out down in the valley. On the other hand, above me I enjoy one of those spectacular starry nights that hint at the existence of a divinity.

THE SECOND DAY

After a difficult and cold night on a bench, the second day is never easy. But leaving again also means warming up and looking for the sun rising above. Up there, where the eyes can open onto the mountains and the world.

What I see, once I reach the Meidpass at dawn, is unforgettable and I sit for a moment to leave a good impression in my eyes. At this hour of the day nobody is this high, not even lonely hiker with their backpacks.

RUNNING ON ANOTHER PLANET

During the ascent to the Augstbordpass one enters another dimension. After leaving meadows and woods on the western side, the earth seems to have disappeared, only to make way for rocks, small to stumble upon, large to jump over, but rocks and more rocks for kilometers and kilometers. This is perhaps the hardest part of the tour, but also the one that I remember best. Thirty kilometers of rocks surrounded by an infinite series of peaks above 3000 m with unpronounceable names.

As I barely see the Topalihutte, a gray spot in a sea of gray, I am almost moved to tears.

In fact, the view from the inside is beautiful beyond words. From the menu, I recommend their hot broth, which soothes even the most troubled stomach.

A RETURN TO CIVILIZATION

With the descent on Randa with its houses, streets and station, that wonderful sense of estrangement from reality in which I lived for two days ends abruptly. I laboriously reach Zermatt, where I see threatening clouds around the Matterhorn. I have to hurry to avoid getting stuck in bad weather. I am too tired to look for an alternative and I try to move forward as fast as possible, but the climb is demanding and I realize that I am going very slowly.

ALMOST THERE

I know the Theodulpass well (I did Cervinia-Zermatt-Cervinia in training a few months earlier); once past the glacier, the descent on the slopes of Cervinia isn’t particularly challenging, even in difficult conditions. The clouds and the wind intensify. I cover up and carry on, with my feet soaking in the melting glacier.

At that precise moment, when feeling tired and with the weather getting worse, I feel good and I feel a deep connection with nature, with my nature. #reconnectwithyournature

The survival instinct and the desire to savor the silence and solitude of the mountain for the last time drain the last reserves of energy from my body and I climb happily up to the 3315 m of the pass.

This tour inspired our most famous jersey: CERVINO TECH T-SHIRT

PS: if someone wants to train for the Hardrock100 this is ideal.

PS2: if anyone wants to organize a race on this wonderful route, I gladly relinquish the rights to name and page of the FB Matterhorn Ultra Race :-)

TECHNICAL NOTES

The path is normally covered by hikers in several days. For more information on the possible stages you can consult the Tour du Cervin website.

Two (basic) maps are available:

-Tour du Cervin 1: 50000, published by Editrek & L’Escursionista

-Tour du Cervin 1: 50000, published by Rotten Verlag

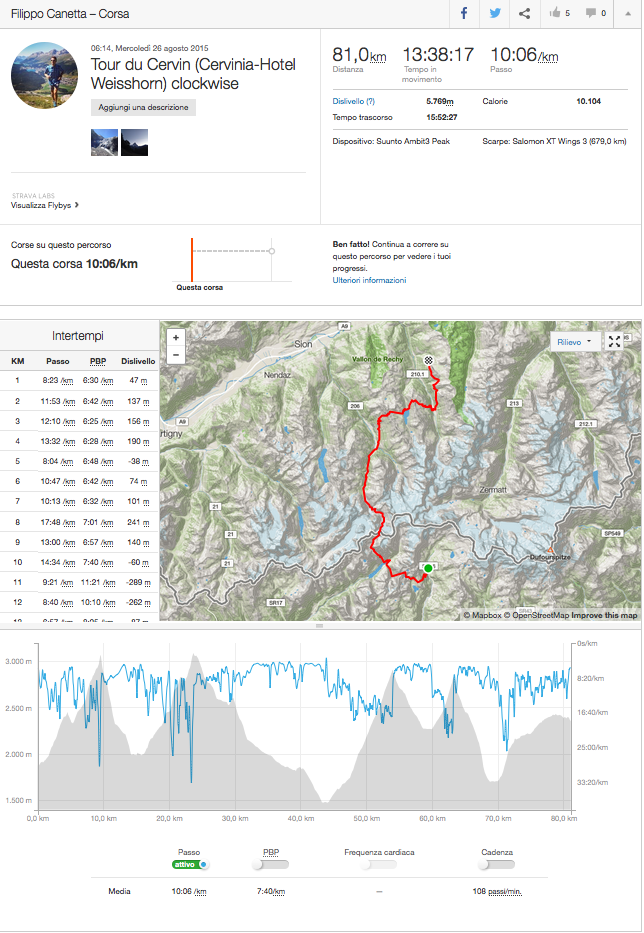

These are my GPS tracks (the only ones I left):