HOW BAD DO I WANT IT?

This time it’s all been so complicated that I don't even know where to begin.

Or maybe I should begin from the reasons why I tried to register for Badwater, ‘the toughest race in the world’.

I despise the heat, but I love doing races without telling anyone and, above all, without involving anyone.

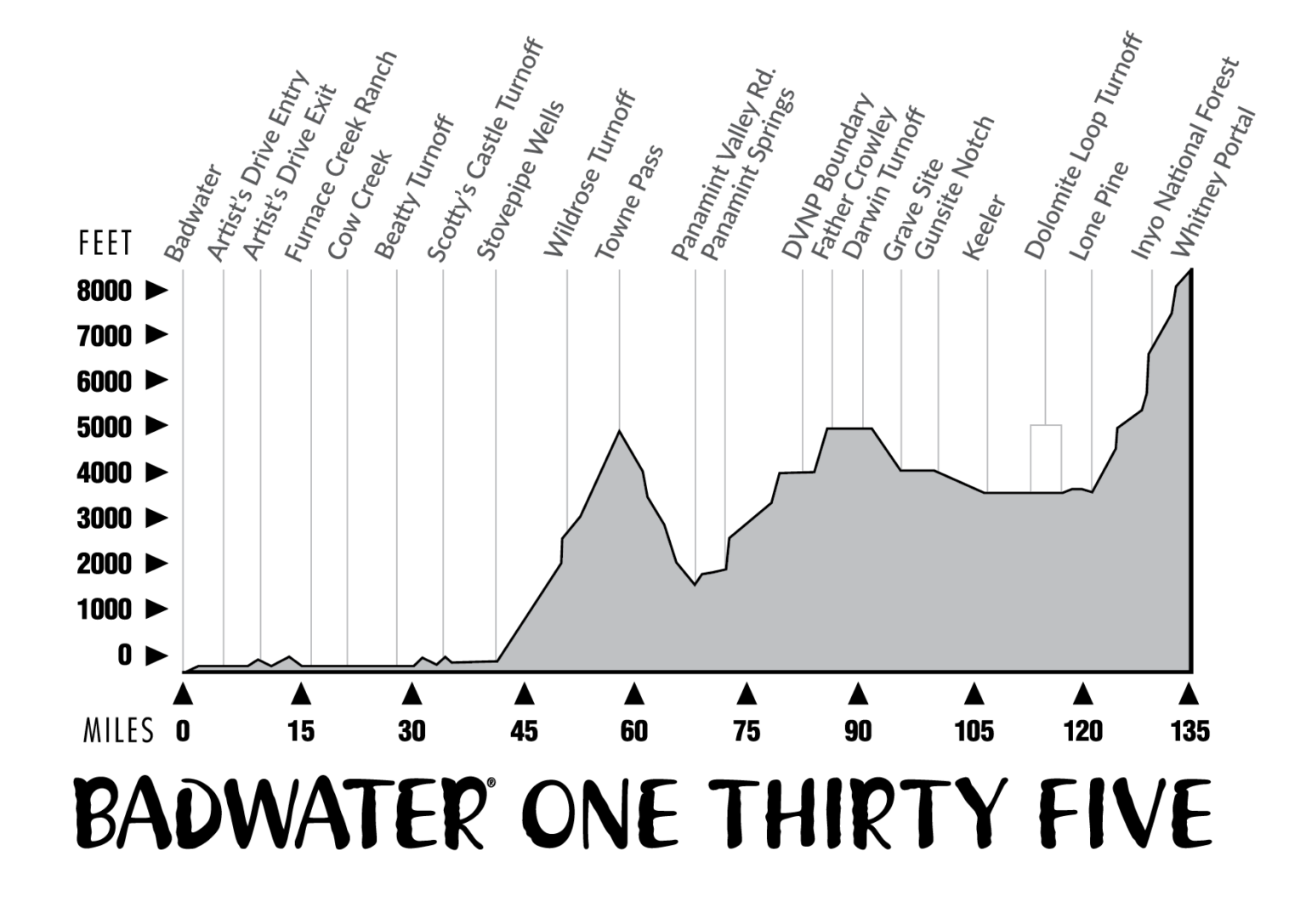

The Badwater race is different: it starts at the lowest point on the American continent, the Badwater Basin, a salt lake 85.5 metres below sea level; it is the exact spot where the highest temperature on earth has been recorded (54°C on 30 July 2013). In July, the temperatures are so high that there are no refreshments or rest stops; therefore, competitors are required to have a support car with at least two drivers for the entire 135-mile race (217 kilometres), to the end of the road. The course then climbs the granite walls of Mount Whitney, the highest mountain in the United States (with the exception of Denali in Alaska), more than 2500 metres above sea level.

Well, at this point you might be wondering why I filled out all the paperwork and provided all my performance data for the past 15 years to be eligible to participate.

I'm still not sure exactly why, but maybe it was because I'd always wanted to take part in a historic race that has existed for 47 years and was run by pioneers of our sport such as Scott Jurek and Dean Karnazes. Perhaps I also wanted to test myself once again with something new and bigger than myself. I think I also wanted to find a new goal for my training, or perhaps simply to see how much more I am capable of suffering.

Practically on the same day at the beginning of February when I received the e-mail confirming that I would be among the hundred athletes selected from all over the world to participate, at the end of a training session my left knee, which had never had anything, suddenly started to hurt like crazy. A new pain I’d never felt and, believe me, I have experienced many over the years. I immediately had an MRI done and discovered that bones can hurt even without breaking. Bone oedema is the response.

I tell myself that there's still time and it's better to stop now than just before the race. I don’t exercise for more than a month, the longest time since I have been doing sport. Unfortunately, the pain doesn’t decrease and every time I put weight on my left leg, I get an intense burning sensation shooting directly into my brain. I am, however, extremely eager and gradually start moving again, putting all the load on my right leg. My body slowly finds a new balance and, in spite of the pain, I manage to resume training: 19, 56, 89, 75, 58, 96 km per week, then 7 days off to see if I carry on like this. My race plan is completely off kilter: according to the original plan I should have already logged some long runs, but I limit myself to a lot of short workouts, several of them on the treadmill. Going uphill gives me less discomfort and at least I begin to simulate a warmer environment, since this was the coldest spring of the ‘century’ in Milan. I try to race in the Trail dei Castelli Bruciati, which doesn’t have much elevation gain and is quite runnable: on the flat and uphill sections I do well, but on the downhill I get passed; I arrive third. Anyway, albeit with suffering, my legs begin to pile up the kilometres. I wanted to race the Nove Colli Running which, as preparation for the Badwater, would have been perfect. However, I opt for the shorter Quattro Colli. I would not have been able to finish the longer race. Fortunately, at least for me, we raced on the only warm day in the whole of May. I arrive third at Barbotto; I’m pretty drained, but also aware that I’ve done a good workout. I try to sign up for the Passatore but they don't accept late registrations.

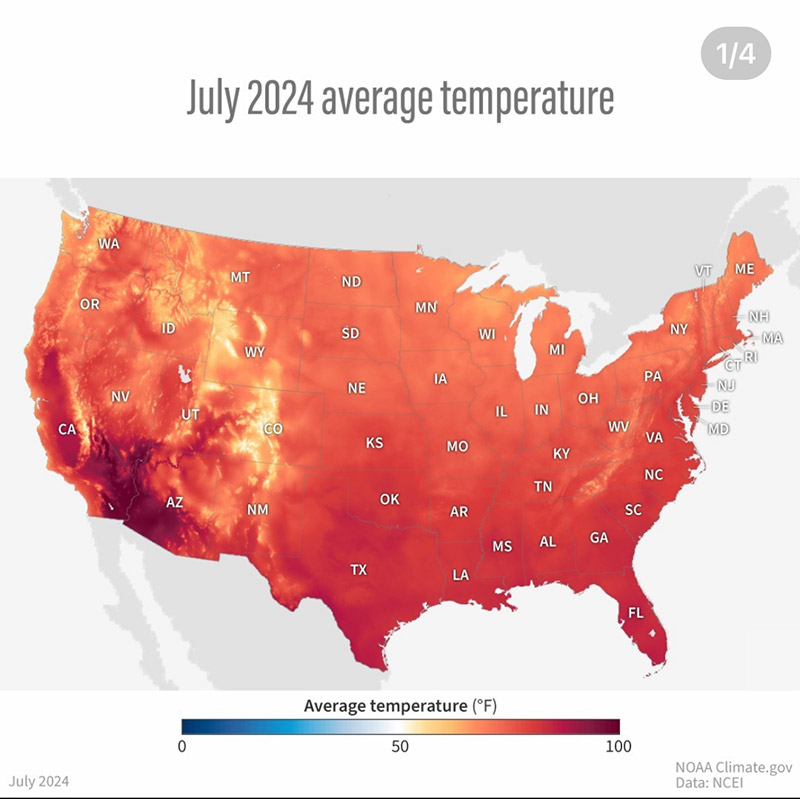

We are now less than two months away, and those beautiful muggy days in the sweltering June heat are still nowhere to be seen. While in Badwater the temperatures are beginning to rise to over 45°C, in Lombardy they’re still not exceeding 25°C.

I go out for a run during the hottest hours of the day, but the temperature is nowhere close to what I need. My worries increase, I need a #cazzomannaggia plan to help me feel more confident that I can make it. I do a long solo 70 kilometres on the Martesana; I get dropped off in Busalla, 60 kilometres from my grandmother's house every weekend we manage to escape from Milan, but even these ‘long’ workouts seem insignificant compared to the 217 km of the race. I don't run as well as I’d like and I always feel the pain, but I have to do better if I want to make it. I manage to do a couple of 120 km weeks but the knee pain starts to worsen again.

We have already booked everything: flights, car, motels, I have involved my friend Giuliano as a crew member. In short, there is no turning back. The stern e-mails from race director Chris Kostman continue to arrive, full of warnings about preparation and the rules to follow to participate. The race already looks pretty complex before the start, and I still don't know what to expect...

In a last-ditch effort, I take part in the 24 hours of Saronno on a track: the plan is to run at least 115 km, corresponding to the first, most runnable part of the Badwater, at a good clip and then see what happens. And what happens is that, before the 100th kilometre, my stomach stops working, with my usual nausea preventing me from eating and forcing me to limit my liquid intake as well. I still finish third with just over 184 kilometres, almost 80 of which I’ve walked. I'm glad I held on and activated my fat metabolism, but for two days I struggle to eat. My stomach is like my empty water bottles.

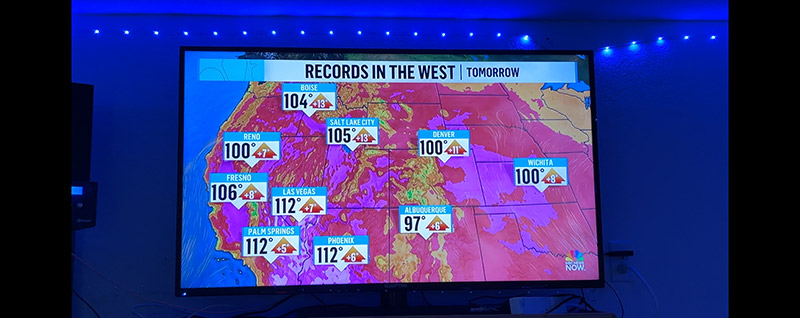

I've covered more than a few kilometres now, but it's the heat that worries me, an ‘abnormal’ heat wave is sweeping California and Nevada: the temperatures in Badwater have already reached 49°C.

I take out a one-month gym membership explaining that I only need to use the sauna. I go two or three times a week until I can resist for an hour at 80°C in four 15-minute sessions.

Finally the adventure starts and I can relax for a moment.

However, our relaxation is short-lived: as soon as we land in Charlotte, in North Carolina, it is absolute chaos. The board of departing flights flashes like a Christmas tree… all flights are delayed or cancelled. It looks like that American Airlines was the airline that was hit hardest by the Microsoft server crash (thank you Microsoft, long live Apple).

We try to stay calm, but we’re getting a lot of updates about our flight's departure time or gate being changed every 15 minutes (we count 114 in 26 hours). Our bags with our worldly belongings in them are stuck in the airport. All we can do is wait until we can leave. We spend one night and one day locked in an airport, with the AC blasting at 15°, eating junk food. The queue to the bathroom is one hour long. The night at the hotel in Las Vegas is gone, and we’ve already paid for it.

I begin to despair; while the obligatory pre-race meeting for bib pick-up is in progress we are still 4000 kilometres away. I write to director Chris Kostman to let him know what’s going on; he replies that if we don't arrive by eleven o'clock on race day I can't start the race. I almost feel relieved considering that, since the organisation does not offer support during the race, we can still run the course on our own: a nice ‘unofficial’ version seems a wonderful way to end this adventure. After yet another delay, it seems that our flight is ready to go.

As we get to Las Vegas it is already evening and we proceed to pick up the minivan that I booked, specifying that it should be white. We are given a black one with a black glass roof that is already scorching, but I am too tired to argue and we must rush to shop some stuff for tomorrow's race. We pick up random things at a convenience store and head to our motel in Death Valley. The temperature indicator on the van marks out numbers in degrees Fahrenheit that are incomprehensible to us, and which keep rising as we get closer. Finally, around midnight, we get to Stovepipe Wells: we first see the service station with a small store, the deserted campsite and a few wooden buildings. We get out of the car to look for the reception and make acquaintance with the ‘monster’ for the first time.

The air is so hot that it is unbreathable, it feels like being in a big oven with the door open. The wind blows constantly and seems to take all the oxygen away from the atmosphere. Irene doesn't stop laughing hysterically. Cecilia wants to go back to the car, Giuliano keeps walking in circles as if in a trance. I’m scared stiff just thinking about what's in store for me tomorrow. I have already experienced the heat, at the Marathon des Sables, at the Western States, at the Spartathlon, in the last section of the Transgrancanaria or at the Gran Raid de la Réunion, but nothing is remotely comparable to this feeling of having no way out, of not being able to survive in the open. A feeling I will never forget.

We try to joke about it as we make our way to the rooms; despite the air conditioner being on full blast everything is warm, even inside the room. We just want to have a shower and go to bed to get our minds off it. Yes, the shower… I fiddle with the mixer which I think is broken and which instead works fine. Even the cold water is 50°C and hot. At least we don't need to use the hairdryer: just two minutes outside and we're dry. Everyone is asleep, but I can't get to sleep and I have a walk outside. The landscape illuminated by a nearly full moon is wonderful and ghostly at the same time, there is nothing but expanses of sand moulded by the wind and sunburnt earth. The only surviving vegetation is low and full of thorns.

We have breakfast in an old saloon and try to take stock of the situation, still feeling anxious. We then head to Lone Pine for bib pickup, and to meet race director Chris. He immediately points out that we are the only ones who did not show up at the pre-race briefing. I show him that we are ready by reciting by heart the 5 pages of race rules, and luckily our obligatory material passes his strict controls. Thank you Emilia and Simone for the super reflective shirts you lent us!

Thankfully, the weather is a bit cooler in the second part of the race, which takes us from our motel to Lone Pine. We collect our poo bags (you can find these on the internet – they're called Biffy Bags) and the third obligatory reflective jersey we had to buy, and head back to the car.

We’ve got just enough time to decorate the car and prepare the thermal containers (one for the ice to drink and one to cool the other drinks, with ice for hat and bandana) and to brief each other that it is time to head for the start. Even before the race start, we have already covered more than six hundred kilometres in the car on the day of the race and we are already spent.

As we approach the Badwater reservoir we meet the competitors who started with the 8pm and 9pm waves; we are in the last wave, at 10pm. I tried to get the organizers to change the start time set by the unappealable judgement of the director but there was nothing to be done: alas, I am among the fastest runners.

As we descend into the valley of death the temperature gauge goes from 115 to 120 degrees Fahrenheit. We are not sure what this corresponds to, but when we get out of the car the air is unbreathable. I am reminded of Scott Jurek's words after his race: ‘I found myself with singed nose hairs’.

It’s impossible to touch the metal barriers separating the car park from the lay-by where only competitors are allowed to go: they are scorching hot.

When we see the super-equipped cars of the other competitors, we are blown away. There’s virtually no phone coverage on the course and many have satellite phones for emergencies and walkie/talkie radios to communicate. Their van boots seem perfectly organised for every emergency, while it looks like we’re here by chance.

This time the ‘Dragon’ to slay is a tough one, I won't hide it; I’ve tried to analyse the strategy of previous finishers. From the splits it seems that everyone takes advantage of the night and the first ‘flat-ish’ part to run at a good pace up to the 67th kilometre at Stovepipe; they tackle the first climb to Towne Pass (+1500 m in 26 km), they run fast on the descent (the only descent in the race) towards Panamint Spring, where more than halfway through the race they slow down, I imagine because of the heat, on the second climb (700 D+ in 13 km); and next they run again, albeit more slowly, up to Lone Pine at the 200th kilometre mark, and finally walk the 1500 m D+ climb to Mount Whitney where, thanks to the second night, it should be cooler.

On paper it all looks clear and pretty straightforward, as I keep repeating, downplaying the difficulties, to my crew who seem increasingly concerned. I have to be honest: I am more worried for them than for myself.

But it’s no use thinking about it now, we've got this far and it's time to start: weight check, ritual photos, national anthem. This is my favourite part of ultrarunning. After months of preparation, studying the route, finding information, paying attention to training and nutrition (apart from the last two days), I can finally focus on running, without thinking about what I could have done better.

I begin to realise that something is amiss when Harvey Lewis, the star of the race, leaves the starting line. Imagine my surprise when he suddenly appears at the last second, all wet and with a bandana full of ice around his neck! He's already finished the race twelve times. And in the YouTube videos I've seen, he never seems to have ice on at the start. I get so worried, as we climbed back up after the start, I shout to my lovely crew, 'Bandana with ice at the first stop!', which unfortunately ruins the start video for all the competitors.

Photos by Manny Olivo

I try to stay calm and assess the situation, which is as absurd as it is new to me, but I’m too stunned to be objective; I set the speed which, according to my absurd mental calculations, based on my Spartathlon and Sakura Michi times, I should keep: 11 km/h, about 5:30 per km.

We’ve agreed to meet every 5 km, and as expected Irene and Giuliano are waiting for me on the left side of the road with their yellow, fluorescent jerseys, with reflectors and flashing led lights, having parked the car on the right side, well outside of the white line with the hazard lights on and the headlights off, as per one of the many rules of the race. I put the ice bandana around my neck, fill the bottles up with water and set off immediately, forgetting to tell them what to prepare for the next stop. I must remember to tell them what to have ready at the next stop so that they don't get too stressed. After 5 more km I quickly refuel and tell them that it's better to have ice in the hat too because my head is frying and it's starting to hurt. Scott Jurek's words ring in my head: ‘I felt like a red-hot iron was bludgeoning my skull from the inside’.

I ask for salts, even though I can't tell if I'm sweating or not. It is so hot that everything dries out immediately. I've read plenty about taking salts and electrolytes, but having never used them, I don't really know what to do.

I can't really assess the effort I'm making in relation to the speed I'm keeping because this dreaded hot wind is blowing right in my face and I can't tell if I'm running uphill or downhill. The gradients of the road are minimal, but the course is never flat and at night it is very difficult to gauge them.

At the next stop I also put on my endurance hat with ice and start off with the handheld bottle filled with electrolyte drink. Usually the head hurts from the cold ice in the first few minutes, while here I keep checking if there is ice in the hat because I don't feel any benefit.

I manage to overtake a few runners, but others pass me at crazy speed. I can't tell if I am catching up with those who left an hour earlier or if these are athletes who started with me. The situation is quite confused and chaotic and it's making it tricky for me to figure out what I'm doing.

Al primo check-point di Furnace Creek (che nome evocativo!) mi sembra già di essere in ritardo sul mio piano di battaglia. Con un colpo da maestra Irene riesce ad acquistare un paio di sacchetti di ghiaccio senza che io debba perdere il contatto con la macchina, intuisce che di ghiaccio ne avremo bisogno più del previsto. Tutto il mio corpo si sta surriscaldando, chiedo di ridurre la distanza tra le soste, quando non vedo la macchina mi sento perso e in pericolo. Mi gioco il jolly della seconda borraccia con ghiaccio per bagnarmi oltre alla bandana e al cappello pieni di ghiaccio. Avevo pensato di usarla solo dopo la comparsa del sole. È l’una di notte, dovrebbero essere le ore meno calde ma la temperatura non accenna a scendere, e io sto già usando tutte le mie armi per abbassare quella del mio corpo.

I can't eat much, but the hydration that worried me so much seems to be working. Instead, I'm having fits of sleep that I've never experienced before. Usually, in longer races, like the PTL, I never sleep the first two nights. But here I stagger and struggle to follow the white line on the road. I don't even realise it, but I'm slowing down. At the 34th km I sit on the boot of the car for a few minutes. Something is not right. I keep looking at the flashing lights of the parked cars, hoping to find mine. Those red lights going on and off in the dark are freaking me out a little bit, to be honest! I'm a little worried because my crew aren’t sleeping. If I reduce the distance between stops, it'll be even harder for them to doze off.

In the months leading up to the race I tried to prepare myself mentally for it all by visualising in as much detail as possible what I would experience, but in this case reality far exceeded my imagination. It’s as if all the training sessions, the hours in the sauna, all the messages of encouragement from my friends, the desire not to embarrass myself in the eyes of my daughter have vanished like an ice cube on this hot asphalt: I remember nothing.

A great tiredness is taking hold of my body, I try to react but the more I push, the more I struggle; I’ve lost my sense of reality. I try to take a break to eat something, but I gag and hurl out the morsel in my mouth; the gag reflexes are so violent that blood comes out of my nose. A scene I would have loved to keep my family and friends from. I feared it would happen, but hoped that this moment would come around the hundredth kilometre and not the thirty-seventh! Distraught and pissed off I get up and set off again. My stomach is empty but at least it gives me respite for a few kilometres. I keep sniffing, I don't want the organisers to see the blood on my shirt and maybe stop me at a medical check-up. I pour water into the palm of my hand and inhale it through my nose to try to breathe. There’s a lump of blood and sand in my throat and I struggle to swallow. I carry on for a while in this condition but the fits of sleep are gradually shutting me down. It’s as if my brain has invented a new ruse to make me stop.

I thought I was ready for anything, but I wasn't prepared at all for these sleep crises. I feel old and tired. My brain wins in the end: at the 44th km I fall asleep. I don't know how long I dozed but I still feel sleepy. I advance a few kilometres but I need to stop again; as soon as I sit down I fall asleep. I am so angry and sorry for not being able to do better than this for my crew that at the check-point of Stovepipe Wells (67th km) I have an uncontrollable crying fit.

I feel so sorry for those close to me and I am willing to retire to stop the sad show to which I am subjecting them. While I am crying on the car seat, Giuliano has changed and is ready to pace me to the next check-point at the eighty-fourth kilometre, where the time barrier is set for 10:00 a.m., two hours less for us who started with the last wave. He came all this way to help me and to share a few kilometres of those endless straights. I don't think I will make it there before the time limit, my stomach is like my empty water bottles, but his gentle enthusiasm pushes me on. It is the first time in my life that I have struggled to make a time barrier and the ascent, although slight, seems insurmountable. The sun has already risen and it’s beginning to bake our backs.

Photos by Manny Olivo

Chris, the race director, is there. I'm sure he’s bet with one of his people that I wouldn't make it there in time, when a few minutes ahead of the time barrier Giuliano and I run past him.

My stomach is still struggling, but this little milestone fills us with joy. We stop for a long break, without looking at the clock, and regroup. Now the crew and I are one, I see them eating slices of the delicious prosciutto brought by Giuliano from Piacenza and it seems to me that the general mood is rising and their faces show some optimism.

The crew accept my weakness and I feel more relieved.

We know that the road is still long, very long, and that the temperature will continue to rise, but little by little we can try to make it. All my plans are out the window but we’re setting off on a new adventure.

The ascent to Towne Pass is very long, but, being used to the climbs of trail running races I’m quicker than the other runners, I overtake a few of them and I get a little spring in my step as a bonus. A staff girl in a car warns us to wear a jacket at the top of the pass. No sooner do I start to imagine the wonderful fresh breeze that will pervade me as soon as I reach the top, than a swarm of bees buzzes around me without giving me a chance to breathe. Convinced that it is less hot on the other side, I let myself be fooled and misunderstood the warning (bees/breeze – got it?). It is useless to try to chase those bees away, there are too many of them, the only thing to do is to keep calm, deploy the neck shroud I put over my hat to protect myself from the sun, and hope that as I run downhill they get tired of following me. The situation is quite grotesque… we also need to endure the bees; I think it was Chris’s ploy to make the race even harder. Luckily I have the long sleeve jersey that I keep wet to protect me (I made a jersey with the Race Fabric and the NOT NOW lettering that turned out to be excellent for both sun protection and freshness).

The only real descent of the race comes right after the pass, about 1000 m of negative altitude change in just under twenty kilometres. I run almost all of it, angrily. I finally feel that my advancing makes some sense. As I descend, I feel the heat rising from the valley, embracing and enveloping me; even the air moved as I run is boiling hot. My quadriceps, which should be used to descending, are burning and melting like butter in the sun. I'm afraid that probably due to the lack of intake of calories my physique has not only burnt fat but also eaten up some of the protein in my muscles.

I get to the bottom of the descent feeling even more confused than before. It was supposed to be less hot and instead I seem to lack air to breathe, it was supposed to be the most runnable part and my legs are so shredded that I struggle to run the flat section which separates the end of the descent from the next climb. In the car it looked runnable and the day before the temperature was almost acceptable. It is a blow to my mood; I look at the data on my Coros (I also have a pod on my foot that measures temperature) and for the first time since we started I see the temperature screen indicate 50°C. The heat is oppressive, absurdly claustrophobic, in complete contrast to the wide open landscape of the valley. I realise that I’m in a tough spot here and that I can only resist as long as the litre of water I carry with me lasts: a few dozen minutes. Running at 40° and and at 50° is a totally different experience.

Photos by Manny Olivo

We aim, and I say “we” because by now this has become a collective adventure and no longer an individual one, to get to Panamint Spring where we can get petrol, refuel with ice and find some food for the crew. I send the car forward and walk the three uphill kilometres to the service station. When I get there I realise that something is amiss: Giuliano is alone getting petrol, Cecilia is on the phone (poor girl, it’s the only place where she gets some signal), Irene is running, like a big city woman at rush hour, from the convenience store to the restaurant and from the restaurant to the convenience store shouting that they’ve run out of ice. She is seriously worried because the next refuelling point is 80 kilometres away. They’ve had enough of being in the car, but at both places there is no air conditioning and it is impossible to stop. Conversely, I am quite calm and lucid, happy to have laboriously passed the halfway point of the race. With my emergency $10 I head back to the service station to buy ice cream and water. When they see that a competitor is buying his own food, the other crews compete to offer me a snack. Happy as a kid who’s saved his pocket money, I sit in the shade eating ice cream and sipping cool water while I try to figure out where the others are. I no longer see them, I go to the car and change my shoes. My Diadora Cellula have held up wonderfully up to here but in the last stretch of the descent the midsole has melted slightly; I could go on using them, but having another pair, I change them together with my socks. I am ready to set off again but I can’t see anyone in my crew. I look for them and tell them that I am setting out for the Father Crowley ascent, thirteen kilometres in which the car, because of the meandering road, can only stop at eight spots designated by the organisation. I climb slowly but steadily, the evening is calm and the traffic on the pass is non-existent; for the first time since I set off I am enjoying the landscape and the sunset with the flashes of a thunderstorm in the distance. We are rationing the remaining ice but now this doesn't seem like a serious problem.

On the asphalt I see the typical serpentine traces of those who pee without stopping. I remember doing it to avoid being caught by the second or the third in races, now I do it by sitting on the car footboard or the rear bumper. How times change...

Giuliano escorts me through the last few hairpin bends, where we hope to find the car at each turn, but we no longer see it.

With no water left we arrive at the pass and we find all crews by their cars, waiting for their runners. There are about twenty of us carrying on more or less at the same pace: by now we know and greet each other every time we meet, like a convoy which slowly advances towards an invisible point above a mountain. Irene manages to get half a bag of ice from the ambulance following the convoy.

The second night also was a bit of a shock: I cannot fathom how it is possible, but I am still feeling drowsy despite all the time I have slept.

I splash ice-cold water on my face to try and keep myself awake but this doesn't work and after ending up a couple of times in those damn prickly bushes that line the road I finally stop and fall asleep. In the night a few drops of rain fall from the cloudy sky eclipsing the full moon. The raindrops seem warm too; they only raise the humidity and make the air even more unbreathable by releasing a rubbery smell from the asphalt.

I try to eat a bite every five kilometres and thanks to a slight downhill stretch I manage to keep a decent pace. Every time I get to the car in the dark of the night my heart cries for my crew. I see them sleeping on the seats in the dark; unfortunately, when the car stops, the doors lock and when I wake poor Giuliano who opens the boot lid for me all the lights come on and the car lights up, waking everyone up. Note to self: next time, remember to keep the doors unlocked and deactivate the automatic light that comes on when you open the doors.

I feel really sorry for them, but I want to take advantage of this moment to cover as many kilometres as possible. I’m actually feeling quite well and with the last of my strength I want to run all the way to Lone Pine.

When we are at about fifteen kilometres from the town, the nightmare of anyone crossing Death Valley materialises in the form of an orange-glowing light on the dashboard: the tyre pressure alert. I was very much dreading this moment. (I only learn at the end that the oil alert had also already lit up). Without wasting any time, Giuliano gets ready to run with me, we load his rucksack and take as many water bottles as we can carry. We say goodbye to Irene and Cecilia, who are leaving, trying to get to a service station before the front left tyre deflates completely.

Photos by Mike Trimpe

We are alone on the endless straight that separates us from Lone Pine; the temperature continues to rise and already seems unbearable. For the first time since we started, Giuliano seems to feel fatigued and I am the one joking about it.

We drink with small but frequent sips and I stop wetting my head and shoulders so as not to waste a single drop. We are ready to beg for some water from another crew, when among the waves of heat on the asphalt we spot the black silhouette with the number 93 of our car. We rush into the boot and this time too we are safe. The tyre wasn't punctured, the tyre specialist had taken it apart, checked it and re-inflated it, says Irene. But we only want to guzzle liquids, even if they are no longer cold. Just after turning the car in the right direction the alert light comes on again. Probably the tyre repairman was distracted by Cecilia's fancy hairy slippers and didn’t do his job properly. Irene quickly decides to go back to the tyre shop.

We're back to being on our own, but the village is getting closer; when we turn onto the state road we're hit by a wall of noise from cars and trucks after all that silence in Death Valley. I haven’t realised before how peaceful that wild place was. We make our way to the second to last checkpoint, where I see the times of the winners. I'm in awe of how they managed to run so fast in those conditions. My admiration for them is boundless.

We are wiped. We haven’t heard from Irene. Before tackling the last climb we rush into the only supermarket in Lone Pine, where ironically two huge freezers full of ice bags greet us as we enter. We don't need them any more now, we eat a disgusting ice cream and fill up on liquids, which quickly get warm while we’re eating the ice cream. Never mind, I'm curious to see the ‘trail’ variant of the route, a change caused by the destruction of the road in the November flood (note to climate change negationists: have a look around here to see what's going on).

Giuliano is (quite rightly) tired; I just want to finish the race and see Chris's face at the top of the mountain. We’ve been warned that the trail is technical and advised to be careful. We’re now more relaxed, and as we approach the finish line we start joking about how ‘technical’ the trail is compared to some passages of the Ferriere Trail Festival trails organised by Giuliano, and we have a good laugh about it.

Having completed the trail section, where we overtook a Japanese competitor and his pacer, our happy moment crashes when we see the asphalt climb we’ll have to tackle without a support car. We’re wandering in the middle of the roadway when Irene comes up to us in the van, honking her horn at full blast and with a brand new tyre.

Photos by Mike Trimpe

Giuliano sits in the boot, in what’s been my seat this whole time, and gobbles down one of the last cans of Schweppes, which we elected as the star drink of the entire trip. Although we can’t see the road going up the mountain, we know that there is not much longer to go and that nothing can stop us, not even a flat tyre. We started this adventure together – and together we will finish it.

As we turn a corner, we see Harvey Lewis running towards us on a runner's high. But how is it possible? He, who was among the best athletes, what is he doing here and why is he running downhill? He tells us that he had to stop and sleep, and that he set off again the next day. He added that it was an incredible experience and that he hopes it will be the same for us too. We find out the next day that, in true #cazzomannaggia style, he wasn’t happy with his race and he decided to run back to Badwater. Harvey, you’re one of us!

The climb that I had envisioned myself covering during the first night according to my plans, however hard, is now a mere formality. I let the car go, so they can wait for us at the finish line. We finish our adventure together, all four of us crossing the finish line, as per tradition, under Chris's amazed gaze. He cannot understand how Ceci could have crossed the valley of death in fancy furry slippers. I think it's a fitting joke for not believing in us, bless him!

Photos by Chris Kostman and Erika Small

The race director was right, this is perhaps the toughest race in the world. When I jokingly tell him this at the finish line, with his impassive face he replies: ‘I know.’

Sure there are longer races, races with more positive elevation gain or on more technical terrain, but nothing compares to Badwater135: there is no escape from the heat.

Photos by Chris Kostman and Erika Small

I wanted to arrive exhausted, destroyed after having given everything I had in what will probably be one of my last long races; instead, at midnight I am still on my feet, wandering around the deserted streets of Lone Pine with Cecilia, trying to figure out what I did wrong.

To end on a high note, our return flight has been postponed until the evening. The plane will also leave with a lower fuel load because of the high temperatures in Las Vegas. We need to refuel in Calgary in Canada and so we miss our connection in Frankfurt. I'm glad I'm not the only one having trouble with the heat.

In 2024 the percentage of finishers was 76.3%, compared to a previous average of 82%.

I'm starting to feel the urge to race it again but it may never be a shared experience like this.

I am without a current race goal. What do I do now? I'd love to hear your advice in the comments.

WATCH FULL VIDEO HERE (warning, strong images)

I always thought running was an individual sport. This time, however, without the support of Giuliano, Irene and Cecilia I would’ve never made it!

Photos by Chris Kostman and Erika Small

Ho chiesto loro di descrivere le loro impressioni su quest’avventura collettiva:

I asked them to describe their impressions of this collective adventure:

GIULIANO

Badwater means endless intense feelings...

On the evening of our departure we were in Stovepipe Wells, right in the heart of Death Valley. We were busy with the last preparations before driving to the start line, when suddenly a sandstorm hit. making the sunset even more beautiful, but it was also unsettling, thinking of what was to come. But this was only the beginning.

During the race, I experienced a lot of surreal moments, but the one that really stuck with me and taught me the most was seeing how, no matter how tough things got for Filippo, he always found a way to stay calm and carry on.

At last, even though we'd known each other for a long time, going through something so personal and deep for over forty hours made our friendship even stronger and more dependable.

IRENE

Tick, tick, tick, that's the sound that accompanied my hours of Filippo's race. It's the sound of the car's hazard lights, flashing while we were waiting to give him shelter.

Shelter, assistance, giving him back his strength. I have seen Filippo race many times in countless environments and conditions, I have seen him focused, desperate, agonising, fighting, but this time it was different for a reason that until I was there I had not understood: how he was literally depending on me.

It was such a great team effort. My tendency to keep on top of things was really put to the test. Everything had to run like clockwork to accomplish this feat; everything from water supplies, ice, to a car that was always running, petrol, how far he was from us, those few food-stocked places, all against the ferocious heat. On the second waking night I had a couple of little paranoid moments, especially when the ice had run out. Or maybe it was a bit of tiredness, but I understood what it means to live in the here and now that everyone goes on about. Those 40 hours were truly a great “here and now” moment for all of us.

It was such a great feeling crossing the finish line together, hand in hand.

CECILIA

It was really blown away by this amazing experience! There were a few things that really stood out for me. The heat was there all the time, and it was so impressive to see how the body reacted to it, both for the runners and the crew.

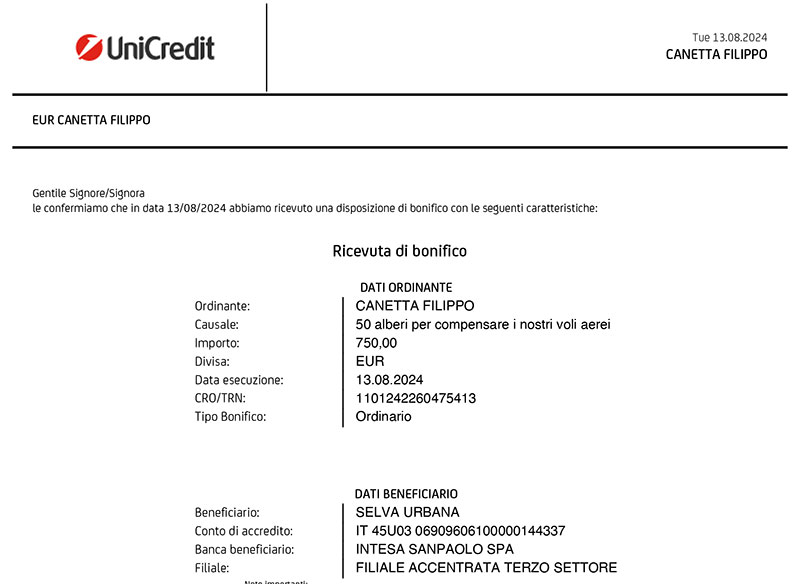

Although I know this is not the solution, I made a personal donation, in addition to Wild Tee's, to Selva Urbana to compensate for our CO2 emissions. Selva Urbana is the non-profit organisation we have been working with for 8 years.

Unfortunately, air flights are a huge source of CO2 emissions and these 50 plants will take about 20 years to compensate the carbon footprint of our trip. Just to give you an idea, 4 people travelling to and from the US with stopovers in between emits about 15 tonnes of CO2, while one plant absorbs 15 kg per year.

For geek only:

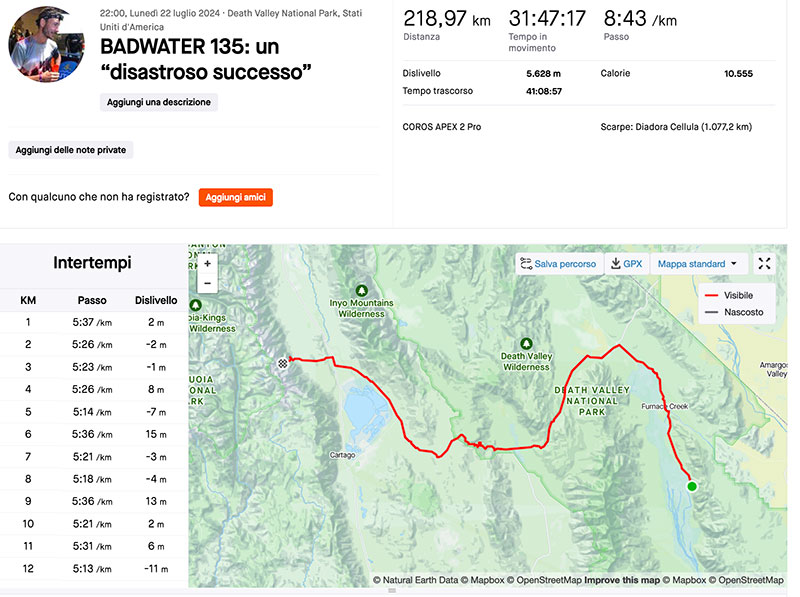

During the 219 km and 5600m elevation gain, covered in 31 hours on the move and 10 hours resting, I used:

-3 jerseys from Wild Tee's RACE collection: a sleeveless, a T-shirt and a long-sleeved jersey

-1 pair of Bryce 2.0 shorts by Wild Tee

-1 Endurance hat by Wild Tee and a prototype neck cover

-2 pair of Rockies Wild Tee socks

-1 COROS Apex 2 Pro course with Pod 2 for temperature measurement

-1 sunglasses ANVMA 99 of Alba Optics

-1 pair of Diadora Cellula for 120 km

-1 pair of Hoka Clifton 9 Wide for 100 km

-4 hand flasks: 1 HydraPak Skyflask Speed, 1 Ultimate Direction AMP, 1 Nathan Quicksqueeze and 1 Camelbak Quick Grip Chill (the best of the 4)

-I drank about 20 litres of water with 2 sachets of salts and 1 of Maurten and 10 litres of soft drinks (Coca-Cola, Fanta, Sprite, Ginger Ale, Schweppes, iced tea)

-I ate: 3 bars, 5 gels, a slice of bread, 4 Flauti, 2 packets of Crackers, a few bites of Beef Jerky, 2 slices of ham, 1 peach, 2 tubs of fruit in syrup

-ho mangiato: 3 barrette, 5 gels, una fetta di pane, 4 Flauti, 2 pacchetti di Crackers, qualche boccone di Beef Jerky, 2 fette di prociutto, 1 pesca, 2 vaschette di frutta sciroppata