Here’s my tale of the 39th MdS, 'The Legendary': 4 friends, 250 km,6 stages to be run in self-sufficiency, 1 Sahara Desert.

It's hard to admit, but as I’ve said before, something in me is broken and I don't think I'm the same anymore.

At Western States 100 in 2023 and even more so at Badwater 135 in 2024 I hadn’t been feeling up to the task anymore. It was as if my mind was behaving as usual, setting ever more ambitious goals for itself: finishing Western States in under twenty hours and Badwater in under thirty. Meanwhile, my body was begging me not to strive for these goals. I was no longer ‘in the zone’, with that unique feeling one gets when running to achieve their outrageous dreams.

On top of that, a number of ailments I’d never had before (first one knee, then the other) made me seriously think I could no longer run and prevented me from planning and training for new goals. Luckily, my passion for Wild Tee consumes me completely, leaving me little time to feel sorry for myself.

I know full well that these can hardly be classed as the 'big issues' in life, but there is no denying that being able to run is crucial to me. It is one of the few things I am proud of. As I review my race stories for the podcast I have wanted to make for at least three years, I realise how much my situation has changed.

I am getting older and it is very difficult for me to accept that.

However, at the lowest point of my so-called "sporting career", the day had come to keep a promise I’d made to a great friend of mine, Simone, whom I met thanks to my first Marathon des Sables, in 2018. For him, after so many years of waiting, it was finally time to go for it, but would I be up to it? Would I be able to run 250 km alone in the Sahara and sleep on sand for a week?

With zero chance of training after knee surgery, I had to take a big bite of humble pie and give up any dreams of doing well in the race.

As it happened, Simone and I were joined by Luca and Floriano, forming a motley crew which we dubbed 'NOT NOW' and, as they say, ‘Trouble shared is trouble halved’.

Almost all of us work in the world of running, but in no time at all we managed to put together some first-class gear. Floriano, Global Running Brand Manager at Diadora, got his company involved in the project, providing the shoes and a budget for content creation. Thanks to this, we were able to enrol Giulia Bertolazzi to film a documentary about our adventure (coming soon). Luca, co-owner of Runaway, put us in touch with Roberto from DangerGrizzly, to design a cutting-edge backpack suitable for the race. Drawing on my experience, I prepared a bespoke set of ultra-light clothing, designed and made by Wild Tee. With my old friend and master shoemaker Marco Zanchi, we made special gaiters that we built into the shoes that I had Diadora send me before they were glued together. Thanks to Andrea, a runner friend, we got in touch with Akta, an Italian startup company that produces freeze-dried organic food of the highest quality.

As time went by, I was still not feeling up to the task, but at least we could sport an all- Italian running outfit to make the best teams green with envy!

And without realising it, it was time to leave Italy.

Following a hectic spell at work, I slept through the flight and the twelve-hour long trip on the bus. When I eventually woke up, I found myself in the middle of the windswept sands of the Sahara, under a Berber tent that we’d be calling home for a week.

Back in 2018, 2018I’d mused that the MdS is not just a race, it is an adventure in a unique situation, one we’re no longer used to. The organisation only provides runners with five litres of water a day and a canopy over our heads; we must carry everything else on our shoulders. I had wonderful memories from the first time I raced here, and with a thousand doubts in my head, I was terrified of tainting those perfect memories.

Luckily, I wasn’t alone this time, and seeing the distress in the face of my 'flatmates' somewhat alleviated my own.

We only had a few hours to decide what to carry in the race before handing over the suitcase which we would only get back in seven days. It was a pivotal moment that could lead to panic. Each of us had to carefully balance the comfort given by having plenty of food with a higher weight on our shoulders. Despite our top-class, lightweight gear and food, a full backpack containing supplies for seven days still felt heavy. In the little training I’d had, I'd noticed that my ability to burn fat had decreased and my calorie needs had increased. So I decided to pack as much food as possible, knowing I’d suffer the extra weight in the early stages, to avoid feeling hungry and cold in the final stages when food starts running out.

In the special technical section (at the end of the story) you can find a comprehensive list of what I brought with me.

Leaving the suitcase behind was ultimately a liberation for me: I no longer needed to think about what to take, and what I’d taken I had to make do with. This kind of minimalism relaxes me, after all. I wanted to disconnect as much as possible from my usual routine; I switched my phone off and left it behind as I handed over my suitcase.

The organisation of the MdS changed in 2024; the legendary Patrick Bauer is no longer race director and the pre-start dinner is no longer being offered; the competitors are left to their own devices. As we enjoyed our last dinner of bresaola and home-made bread, we prepared to begin our adventure.

One of the things I’d appreciated about my first experience in the desert was the need to adapt to the rhythms of nature and the sun, rather than those imposed by society. We ate early, around 6.30 PM. At 8 PM, at sundown, we went to bed in order to be ready to start racing between 6 and 7 a.m., depending on the stage. Stage starting times are now earlier than in the past to avoid running during the hottest hours of the day. This may sound unusual for a race famed for its heat, but all the better for us.

The tents forming the circle of the camp seemed closer to each other than I remembered; this gave less the impression of being isolated in the middle of the desert and more that of being at a holiday resort. The 1009 competitors were in fact younger and much louder. I’d had a partly idealised memory of a monastery of tents of sorts, where everyone was focused on their own experience, but then I realised how much trail running and this race had changed with the advent of social media.

This time I had a little trouble adjusting to it all, and while almost everyone was asleep I wandered around the camp, enjoying the peace of a starry desert night. Finally, after a few hours, the silence was total and the sky, without light pollution, seemed very close, the Milky Way almost within reach. I began to think that it was worth coming all this way.

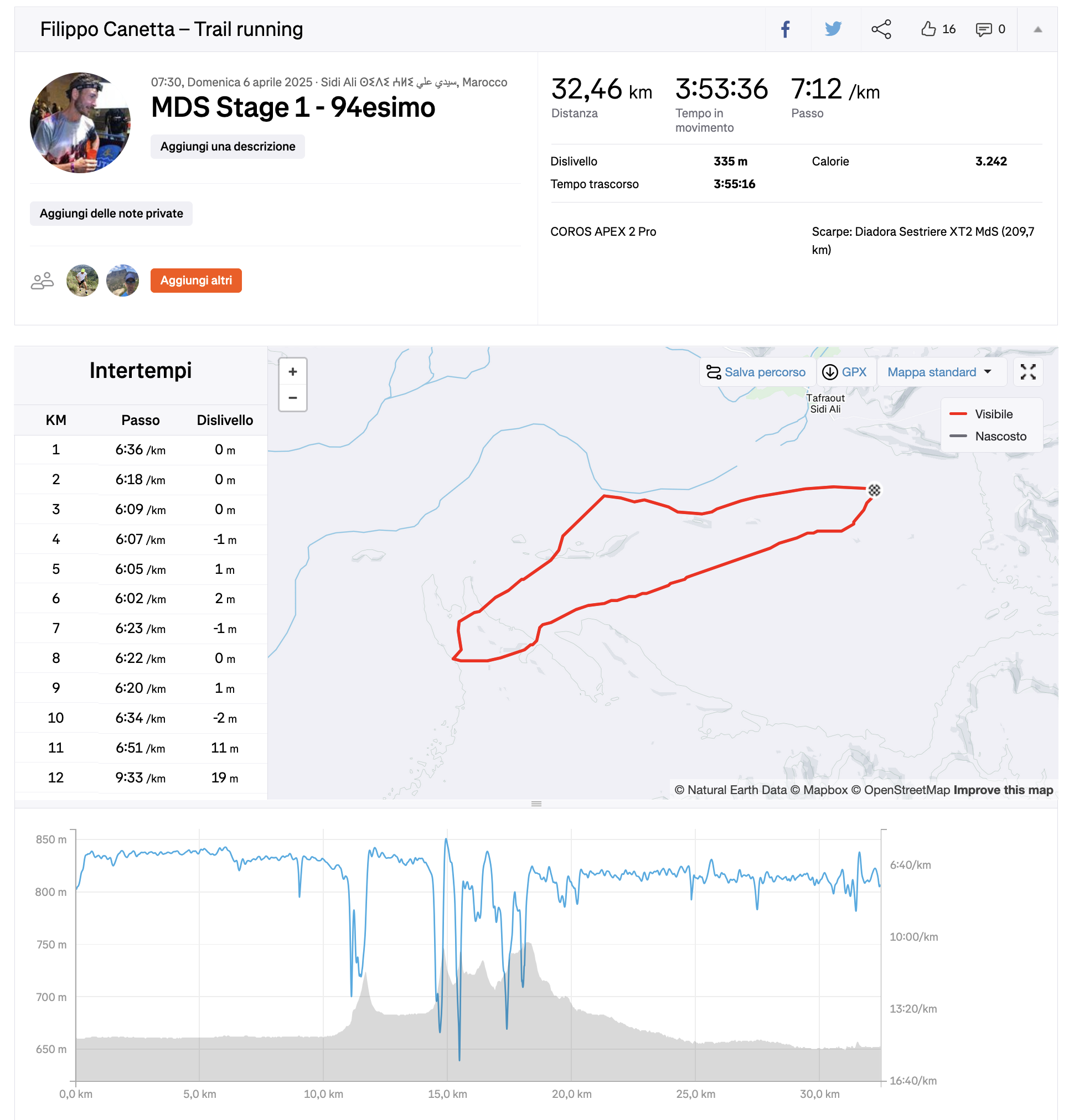

At the start of the first stage, a 32km loop with 312m elevation gain, it felt like we were at the Half Marathon World Championship. Everyone set off at a crazy pace with their huge, wobbly backpacks on their back. I had no idea how my body and mind would handle this race and I didn't want to compete with the others. I didn't even want to be influenced by the GPS, so I started dead last and decided to run at a comfortable pace. I wasn’t feeling at my best, but keeping a steady pace, in the final section of the stage I slowly caught up with many of the competitors who were beginning to see what the desert had in store for us.

Despite the weight of the first day, we found the backpack we’d designed to be stable and comfortable. Not a single grain of sand got through the gaiters integrated into the shoes. The long-sleeved race jersey was cool and lightweight. All my worries about equipment were gone so I could concentrate on what I love most: running.

I didn't want to think about the race rankings, so I tried to capture once again that feeling of bliss that comes from only having to run, eat and rest.

The day was scorching, and it was difficult to linger under the black canopy of the Berber tent in the middle of the day. We tried to move as little as possible to conserve our energy, but even when standing still, we were sweating buckets. The wind-blown sand coming in through the holes in the tent quickly covered us. It was a tricky situation to be in; I hadn't thought of these mishaps. Fortunately, after sundown we could get out of the tent to stretch our legs, as the camp quickly came to life.

At the end of adventures like these, I like to ask my mates what they missed the most from civilisation. My answer is straightforward: a chair. Of the many comforts we lacked, the trivial inability to sit down was the one that worried me the most. Apart from the two minutes a day when we got to sit in the camp's toilets, we had no opportunity to do so for seven days. Come to think of it, we normally spend most of our day sitting: at work, in the car, on public transport or cycling, at the table and on the sofa. Suddenly, it is not easy to kick the habit, and sitting on the sand is not quite the same.

The sun set quickly, we lit a fire and enjoyed our dinner. Akta's freeze-dried food is delicious, the pouches contain typical Italian dishes: rice with peas, buckwheat polenta, grass peas and escarole, maltagliati pasta with chickpeas and pasta with lentils. They are quick to prepare, even with non-boiling water (a great advantage, since water is not easy to heat when the wind is blowing constantly). We were all confident that they would be our prime weapon against going hungry. I’d planned to eat two of these meals a day, except for the longest stage, when I’d only have one. During the first three days I’d supplement with some parmesan, meat and dried fruit.

Some of us, worried about the weight in our backpacks, took less food but ran lighter.

My teammates were dying to hit the sack, and by eight o'clock they were already stretched out on their mats. I feared that each of them was in some way worried about the unusual situation we were in. I, the late sleeper, moved away from the camp with my torch and walked beyond the 'pee line', the circumference outside the tents where everyone has a pee, the amount of which would be reduced over the coming days as my legs became ever more tired.

I liked watching the tents from afar in the evening silence. It was as if I was distancing myself from competing.

This was the third night we’d spend in this camp (the first two were spent adjusting to the conditions), and I was looking forward to moving on and seeing different scenery tomorrow. The fact that the camp was no longer changing location, as it had been in the past, had taken away some of the charm of the nomadic Berber caravan that the MdS represented.

There wasn’t a lot of room in the tent for eight adults; upon my return, I found that my space had been reduced to the bare minimum after my companions hogged some of it in my absence. During the night, increasingly strong gusts of wind seemed to slap the tent canvas, and more and more sand was getting blown in. Even when buried inside the sleeping bag, it was difficult to breathe without swallowing sand. I didn't sleep very well. After a quick breakfast and packing everything back into the backpacks, the other runners were ready to leave. I tend to be late, so I headed for the starting line with the last group. I didn't want to start at the front and have my pace dictated by the fastest runners. Although my backpack was only marginally lighter (by 300 grams), the psychological impact was significant, and I could run more relaxed.

I was dreading the pains that had plagued one of my legs, and then the other, throughout last year, so I concentrated on running evenly on both legs. Running on soft sand seemed to help. The second stage, a 40-km long run with 614 m of ascent, was on varying terrain, and I enjoyed overtaking other runners, trying to optimise my pace according to the terrain and its complications. I remember this sensation pretty well; think running on an unforgiving surface that drains all your energy without returning any. It’s no use pushing too hard when the sand is fine and soft; it's better to move gently and conserve energy for when the ground is firmer. Some rocky sections finally reminded me that this is still a trail race.

Around halfway through the stage, I caught up with Gemma, a British competitor I’d met in 2018. I told her that I wouldn't make the same mistake I’d made years ago when I passed her, only for her to finish miles ahead of me in the longest stage. On that occasion, she had finished third and on the podium. I told her that I’d taken a photo of her looking at a picture of her children while we were waiting to start the second wave of the long stage; she remembered that moment well. You can find the photo in the 2018 story..

A strong headwind was blowing, so we decided to take turns at leading the group. This seemed to work, and the kilometres passed in a breeze, even on the seemingly endless final straight.

When I got to the camp, the field was strangely not ready to welcome us yet, so I lay down on the carpet, waiting. This had never happened before. Under old management, two camps were set up. While we slept at camp 1, camp 2 would be set up. Then, camp 1 would move to camp 3 — it was like a travelling village.

We'd only covered 72 km of the total 250, but the atmosphere in tent 99 was relaxed, and the tension of the unknown seemed to have disappeared from the faces of Floriano and Simone, who were experiencing this for the first time. Luca was a case in point: fresh from a bad crisis during the stage, he wanted to retire. As soon as he reached us, he said he wanted to call a taxi, much to our amusement! He’d been in the sun too long, and after visiting the infirmary he disappeared for two hours. Upon his return, we learn that they laid him in a tub full of ice to lower his body temperature.

I had a thousand doubts about my physical fitness at this point and I was worried about the 83-kilometre stage awaiting us in two days' time. I didn't want to make the same mistake as in 2018, when I’d pushed too hard in the first three stages and then bonked hard; this forced me to slow down and lose a lot of time in the longest stage.

Unexpectedly, we were placed third in the team rankings. These are based on the average of the team members' times. We were just a few minutes ahead of the fourth- placed team. This filled us with joy, but we were also aware that there was still a long way to go and anything could happen.

On the other hand, I was really struggling in the third stage, a 32.5-km long race with 468 m of ascent. I just couldn't get into the rhythm of the day before. The harder I tried, the less responsive my legs seemed to be. I tried not to worry, reminding myself that the race was still long and anything could happen. However, I felt like I was moving very slowly; I knew this was true when some runners passed me in a relatively easy section. I tried not to fall too far behind them, keeping them in sight as the course climbed a rocky hill. At last, since the start of the race, my feet can push on firm terrain. The climb is not very long (with an altitude difference of about 150 m), but it is rather technical. Amazingly, the other competitors seemed to be struggling on this section, especially on the subsequent descent. I finally felt at ease and caught up. I’d certainly lost positions during this stage, but I didn’t know how many, as the organisation no longer displayed the rankings at the end of each stage.

It felt a bit strange having to take everything with you while racing and then return to camp in the same spot. But these are the rules: anyone who leaves something at the camp will not only fail to find it at the end of the stage, they will also be penalised by at least thirty minutes. This is what happened to a Dutch girl who lost third place for this very reason.

They even waited until the evening to display the list of the first 50 runners who would start two hours later than the group the next day. They actually displayed it when almost everyone was already asleep. This was odd, given that it is a competitive race, after all.

Fortunately, I was ranked 55th at that point and I wasn’t not on the list, so I knew I’d start with the first wave at 6:00am and benefit from the cooler morning. This cheered me up and motivated me to do my best.

Strangely enough, I felt great the next day. I knew that the real race begins on this 82.2- km, 690m ascent inline stage. The first three stages had been good training for this one. I felt ready to put myself out there and compare myself with the other runners.

This time, I wanted to start at the front and Simone wished me 'good hunting'. After all, I was there because of him, and I owed him that much. I set off fast, not looking around me; I wanted to create my own personal 'bubble' and only look ahead.

The course kept changing; as we passed through high red sand dunes, we had to climb with the help of our hands. There was no point in trying to advance only using our feet. We crossed desolate grasslands where life seems impossible. We ran on animal trails to remain in the shade of a hill. We saw camel farms and the remains of ancient fortresses, now reclaimed by the sand.

For the first time in a long while, I felt that my body was responding well, spurred by my high spirits and the environment around me. And after what seemed like an eternity, I could hear 'the music' in my head; this, perhaps influenced by the organisers' language, was in French. The song that kept playing on repeat is Stromae's 'Alors on Danse', which is not quite the hard rock I had imagined, but the line 'Et là tu te dis que c'est fini.... Quand y en a plus, ben y en a encore' (And then you tell yourself it's over... When there's nothing left, well, there's more' fit the ultra mood perfectly.

Perhaps it was the lighter backpack, or maybe my desire to keep our team in third place, but I was advancing well, adapting to the terrain I encountered and catching up with those who’d started with the 6 am wave. At around the 40th kilometre, Rachid Elmorabity — the unbeatable Moroccan athlete who would win the MdS for the 11th time this year — passed me at supersonic speed. In practice, he ran 90 minutes faster than me in 40 kilometres. I remembered him from 2018, when I’d tried to follow him for a short distance to study his technique on the dunes. He moved over them as if he were one of those insects that can walk on water with small steps; he was floating on the sand while I sank to my knees in it.

I didn't want to look back and lose my focus, but I expected the top 50 to overtake me shortly. Instead, more than an hour had gone by before Rachid's brother and another competitor caught up with me. As is often the case, it only takes one small detail to ruin an otherwise ideal situation.

Come quasi sempre accade, basta un piccolo dettaglio per ribaltare una situazione ideale.

Unexpectedly, at the fifty-fourth Km aid station, in addition to the usual water, we found a small banquet of dates and dried fruit. I took a handful, which I ate as I set off again. In a situation of scarcity such as the fourth day of the MdS, finding food seemed like an opportunity not to be missed, but after a few kilometres, I realised that something wasn’t quite right and my stomach started to play up.

I began to think that all my calculations regarding time, speed, and position had been going wrong. I had no way out. I had to walk, and a couple of competitors overtook me. In the spirit of sportsmanship, I cheered them on, but I saw the finish line getting further and further away. As I dragged myself along an endless straight towards nowhere, when it seemed all was lost, a glimmer of rationality pierced my negative thoughts, and I remembered Death Valley during Badwater. I reassessed the situation. It would have been at least ten degrees cooler than in Death Valley, and it couldn't be worse than that. I was still well placed in the rankings; if I alternated walking and running, I could still make it. And so I did, trying to clear my mind of negative thoughts. Slowly, the straight path ended, and I arrived at the next aid station. I knew I couldn’t afford to stop, so I quickly refuelled and forced myself to leave immediately.

I focused on following the course markings. I had to try to run again, but I was worried that it would make things worse and I'd become dehydrated. I started to follow a guy who’s caught up with me. I focussed and stayed hot on his heels. When he started walking, I kept on running and held on. I knew I was running on fumes. I'd drunk very little and I couldn't eat, but I was holding on. Fortunately, it seemed that the other runners were struggling too, as they appeared to be slowing down. I could see in the distance that the gap between us remained the same. After all the effort I put in to overtake them at the start, it was time to catch up with them. I found the last of my gels in the side pocket of my shorts and tried to take a sip; it seemed to go down. With about 15 kilometres to go, I could see the camp and the stage finish in the distance.

In a seemingly infinite environment like the desert, you can see things that are very far away. I started to think that I could actually make it. I could still see two competitors ahead of me, and I focused on them. It was very hot, and when the wind wasn’t blowing, I could feel myself sweating. However, I also thought that if I was sweating, it meant that I wasn’t dehydrated yet. I performed a quick calculation and realised that I could reach the finish line in less than an hour and a half. I knew that I was using up my last energy reserves. I tried not to think about the next two stages in the coming days. I didn't have much energy left, but I could make it to the end and I'd think about the consequences later.

I ran with all my remaining strength and, a few kilometres from the finish line, I overtook the two who had overtaken me earlier. I saw one of the elite runners sitting down, trying to call for help with the GPS tracker. I showed him which button to press, and he told me to go. Some sand dunes stand between me and the finish line. I concentrated on finding the best route to take through them. By now, I’d learnt that there is always somewhere to find firmer terrain in the sand, and that is where it is best to run. There was little distance left now; I was exhausted, but I kept pushing, fuelled by 'the music' in my head, until I reached the banner marking the end of the stage. I didn't know how I did in the stage because, once again, the rankings weren’t posted, but I'm happy with how I ran it.

I make no secret of the fact that arriving at the camp when almost no one else is there — partly because the first fifty runners left an hour and a half later — is a very gratifying feeling. It allows me to enjoy the solitude while I recover from the effort. I put my backpack down, took off my shoes, socks and T-shirt, found a shady spot in the tent and lay down to enjoy the breeze. It was a beautiful moment. The camp was deserted and silent. The competitors were still arriving one by one, a few minutes apart. As they passed in front of our tent, we congratulated each other, knowing that we’d just completed the hardest stage of the race. We completed almost 190 kilometres, with less than 70 still to go.

Everything was taking on another dimension.

My teammates finished at different times: first Luca, who’d wanted to retire, but who had evidently benefited from the cold tub treatment; then Floriano, who had performed well in the first three stages but then struggled, arriving together with Simone, who helped him to finish the stage with his collaborative spirit.

Now, a well-deserved rest day awaited us, a rest day those walking the longer stage would need. The atmosphere at the camp was more relaxed, and in addition to the usual five litres of water per day, we were offered a can of Coke. It was one of the tastiest of my life.

We started to feel hungry, but we had to be careful not to overeat and deplete the supplies needed for the last two days. I had already noticed this, but after a few days of poor nutrition, the stomach shrinks, meaning we only need to eat a little to feel full.

OurAKTA bags were doing their job, and I was feeling strong.

Despite the kilometres in the bag, I was feeling more energetic than expected, compared to our hectic 'normal' life here. I felt less tired than usual and had less need for sleep.

In the evening, they only announced the list of the first 50 starters, who would set off an hour and a half later. However, they wouldn't reveal the rankings until the next morning, just a few minutes before the start.

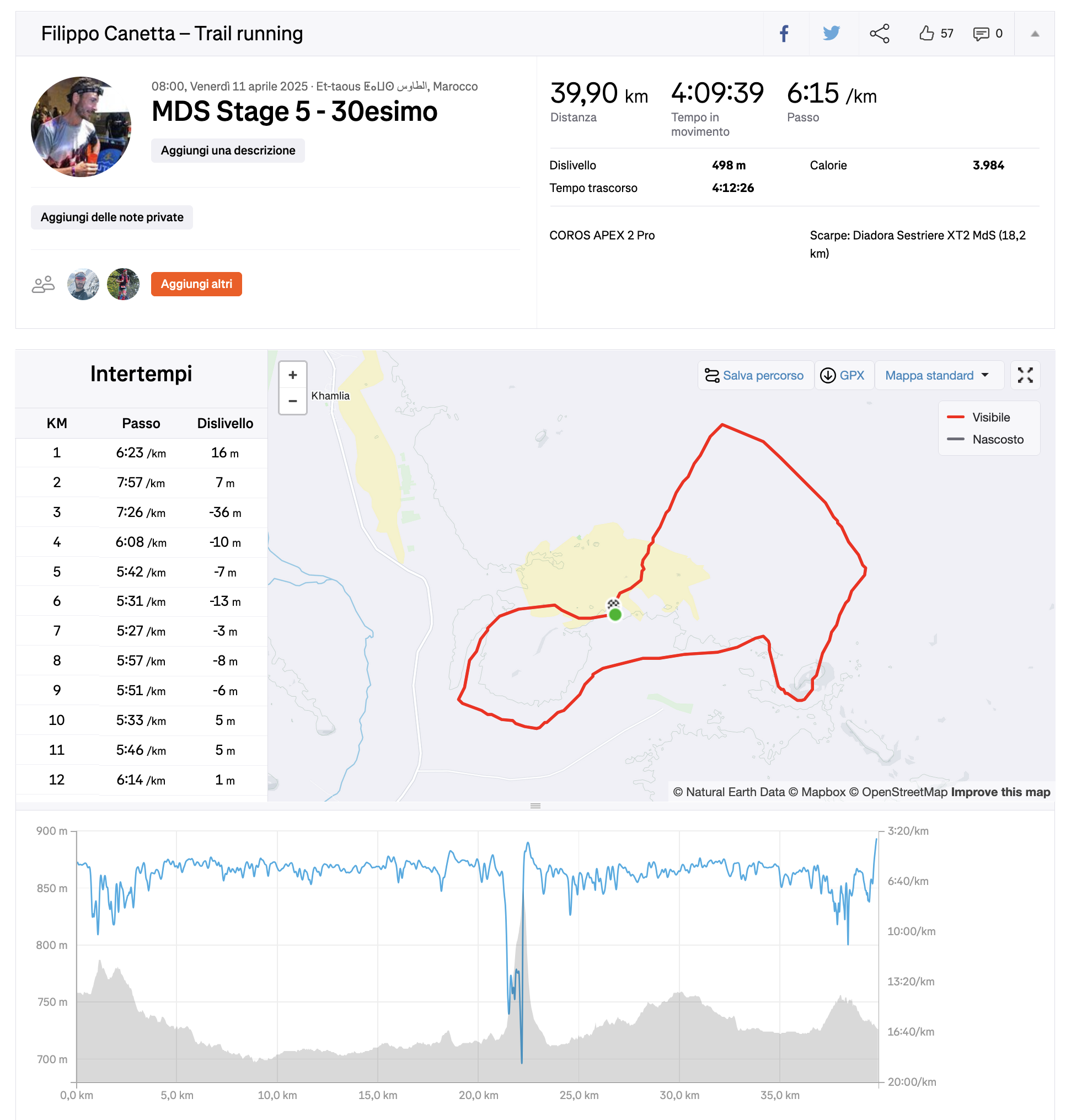

We had a decent lead over the fourth team, and I was third in my age group, just a few minutes behind an Australian runner whose bib number I tried to memorise so that I could keep an eye on him. I was not worried about starting later for a 42.2 km stage with 424 m of ascent, so I could take it easy during the usual pre-start preparations. I also took advantage of the toilets (the only place we could sit!) without feeling anxious about the others queuing outside.

At the start line, there were only a few of us compared to the usual crowd on the other days. I spotted the Australian competitor straight away and caught up with him at the start. I think he noticed me, too, because he kept looking at me. In races, it's common to have an opponent you can use as a reference. In the early stages, you have to study each other to see where their weaknesses lie — uphill, flat, or downhill — and whether they're holding back or pushing from the start.

Feeling good, I decided to try and increase the gap between us. We looked at each other one last time, then I pull away. Before long, I could no longer see him behind me. Even though my body had adapted by the fifth day and my needs were reduced, I concentrated on hydrating and nutrition, which is my Achilles heel.

My plan seemed to be working perfectly; I continued to climb the rankings without any drop in performance.

It was a feeling I hadn't experienced in a long time. When you're in shape and racing with the front runners, it's a completely different experience; it's as if your body transforms in unexpected ways. My daughter jokingly asks me before races if I'll turn into 'a rocket’, even though I've never been fast. It'd been a long time since I felt like this, and it's great. I pushed myself to the limit, and in the end I finished twenty minutes ahead of my Australian friend. I also recovered a few positions in the general classification.

The order of arrival of my teammates changed again: Floriano also recovered, thanks to the food that Simone offered him; he made steady progress. Luca, on the other hand, struggled somewhat in this stage.

Anyway, we were still in third place!

We all laughed and joked as we ate the last of the food. I could feel hunger starting to set in! My calorie consumption was probably higher because of the increased pace in these last two stages, and my stomach was rumbling, keeping me awake.

After breakfast, my backpack was practically empty, and it felt like I didn't even have it on my shoulders.

Only a half-marathon (21.1 km and 202 m climb) separated us from the finish line. Studying the map, we estimated that the route would begin and end with three kilometres of dunes. There were no calculations to be made here; we had to start and finish at full speed.

I tried not to think about anything, visualising instead my arrival and the joy of getting on the bus back to civilisation, as well as the snacks provided by the organisers.

I pushed hard on the first dunes and realised that I hadn't started the GPS. I didn't stop at the first aid station and tried to keep a fast pace on the long straight before the next dunes. I also skipped the second refreshment point and sipped the last of my gel. Crossing the last 'erg' (dune bank) that separated us from Merzouga, where the finish line was located, was no easy feat. The dunes are high, and instead of running on the ridge, we continued to climb and descend; the finish line never seemed to get any closer.

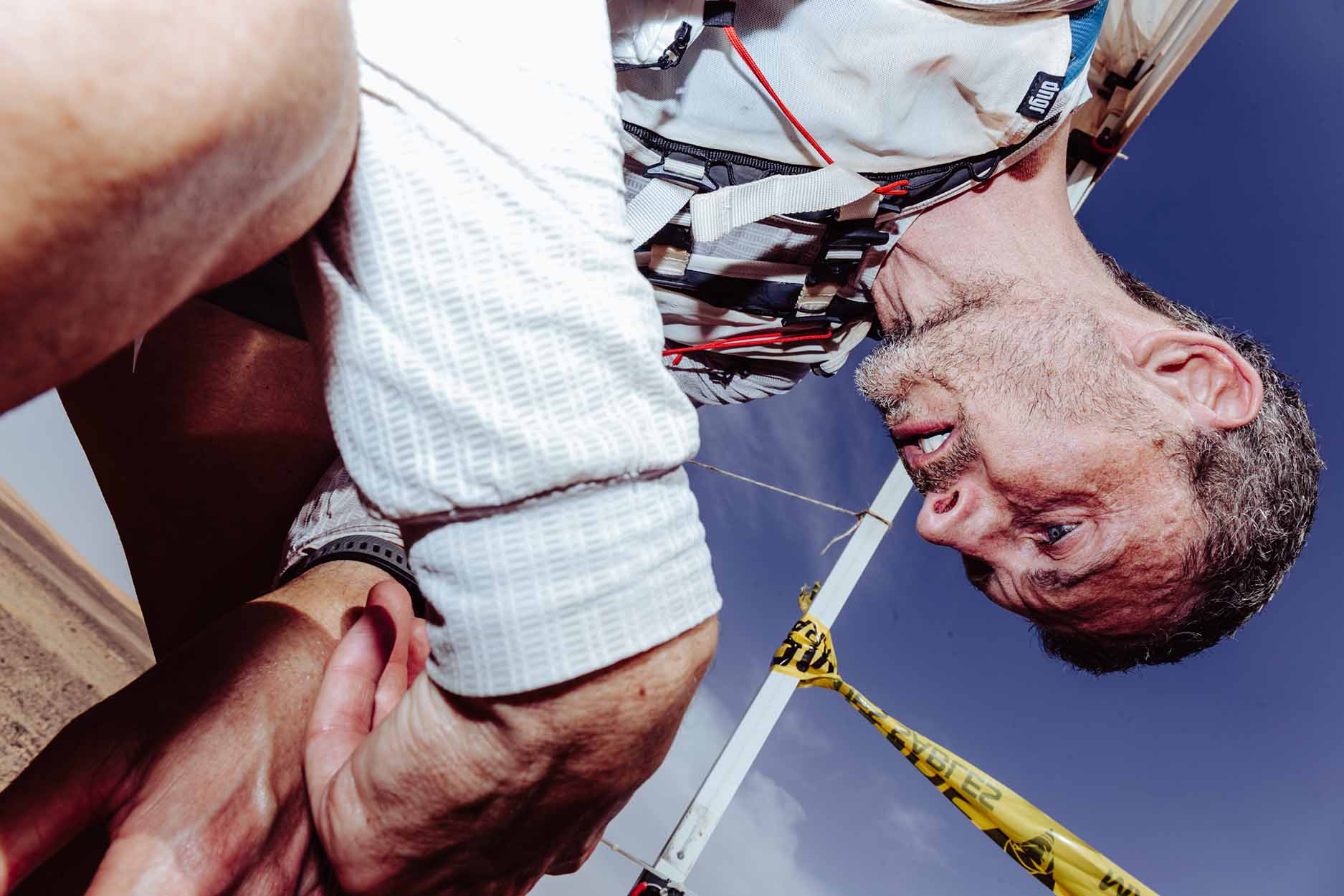

I didn't have any more energy. I struggled up and down the softest sand I’d ever experienced, which absorbed what little strength I had left. My breathing became shallower and my heart started beating faster to capture what little energy I had left in my body. But I heard the speaker, and I knew that sooner or later these ups and downs would end and I would see the arch of the finish line. I could also hear the screams of the crowd waiting for us. I was almost there. One last climb and I could see it: the first seventeen competitors were still within sight.

I sprinted as if it were the last race of my life, because it still was a race and I wanted to honour it until the end.

As always, crossing the finish line is a liberation; all the accumulated tension vanishes as if by magic, leaving a dumb smile on my face. I can smell ammonia when I inhale; it means that I have given everything.

I had no interest in the usual photo ops, so I took out the action cam I brought and ran back to the last dune — I didn't want to miss the arrival of my teammates. I watched them arrive one by one in their now dusty white uniforms, their eyes shining with joy, and I filmed all three of them, getting more emotional about their arrival than my own.

Simone was so satisfied that he was almost sad the race was over. We returned to the finish line, where the four of us hugged each other.

Perhaps I could have dared a bit more in the first three stages, but I had so many unanswered questions. I had more fun than I’d had in a long time, and it was another valuable life experience.

I now miss that wonderful feeling of freedom that only the endless desert can give you when you're self-sufficient.

Credit for (nearly) all pictures goes to Giulia Bertolazzi

Gear:

- DangerGrizzly Backpack (28L - 480 gr.)

- 1 “Not Now” LS Shirt made with our Race-spec fabric

- 1 “Not Now” T-Shirt made with our Road-spec fabric

- 2 pairs of underpants

- 3 pairs of Rockies White/Black

- 1 “Not Now” Neck Cover

- 1 pair of sunglasses with photocromic lenses Wild Tee x Rudy Project “Astral S Gradient Purple”

- 1 pair of Diadora Sestriere XT2 shoes with Wild Tee gaiters, artfully integrated by Marco Zanchi

- 1 Petzl IKO headlamp with spare batteries

- 3 DangerGrizzly Soft Flasks (500 ml each)

- 1 Pair of “custom” Wild Tee slippers

- 2 paper tissues packs

- 2 packs of wet wipes

- 1 Nordisk “Passion One” summer sleeping bag (12°C, you’ll feel cold but it’s featherlight)

- 1 THERMAREST NeoAir Xlite sleeping mat

- 1 toothbrush

- 1 mint-flavoured Marvis toothpaste tube

- Earplugs

- 10 compressed mini-towels (thanks Simo)

- Powdered soap (thanks Simo)

-1 DJI Osmo Action 5 Pro

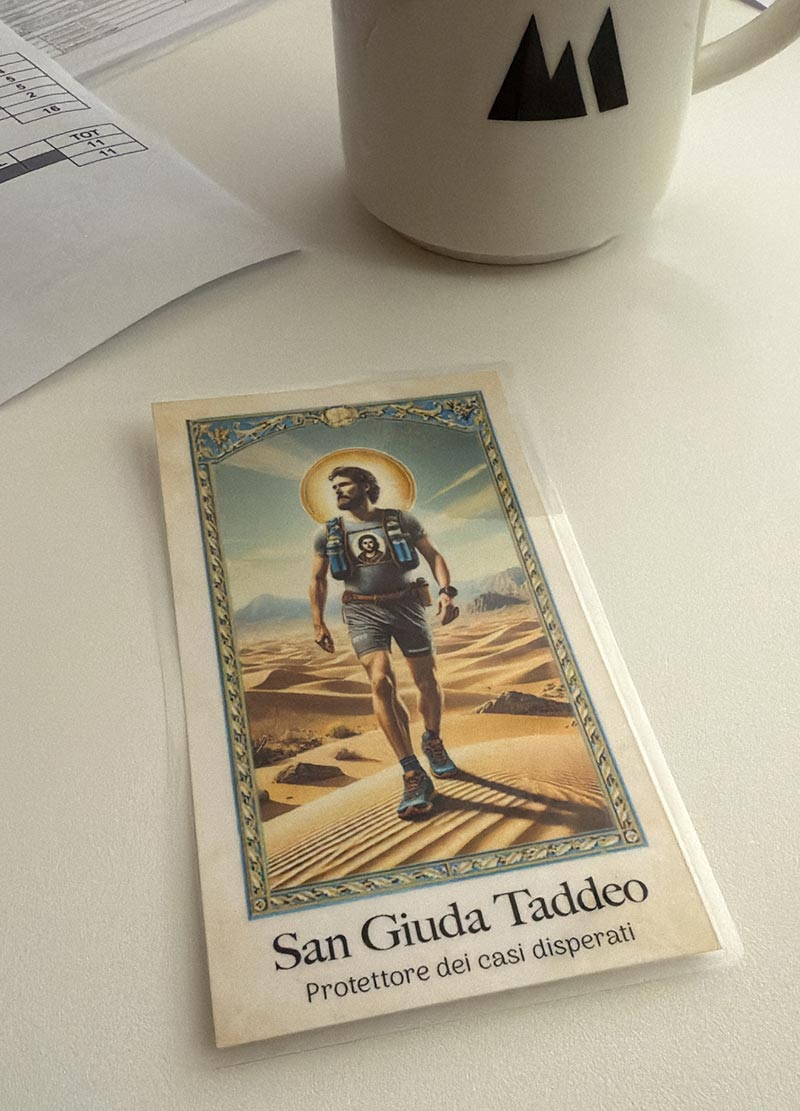

- 1 Saint Giuda Taddeo prayer card, made by our friend Marco Mascetti

Food:

- 12 AKTA freeze-dried food packs (125 g each)

- 3 Grana Padano portions (80 g each)

- 3 Beef Jerky bags (40 g each)

- 3 dried meat portions (70 g each)

- 3 dried fish portions (50 g each)

- 1 dehydrated fruit bag (100 g)

- 6 packs of breakfast muesli (110 g each)

- 8 Maurten Solid energy bars 160 (55 g each)

- 4 Maurten 160 gel bags (65 g each)

- 3 Maurten 100 gel bags (40 g each)

- 3 Maurten 100 CAF 100 gel bags (40 g each)

Mandatory equipment:

- 1 survival blanket

- 1 lighter

- 1 mirror

- 1 cup

- 1 compass

- 10 safety pins

- 1 knife

- Sunscreen

- Antiseptic solution

- 12 stock cubes

- 1 whistle (integrated with the backpack)

- €200 cash

- Passport

All race stages are on Strava: